Wine And Blood At The Beauregard-Keyes House

This story is part of TriPod: New Orleans at 300. TriPod moves beyond the familiar themes of New Orleans history to focus on forgotten, neglected, or surprising pieces of the city’s past to help us better understand present and future challenges.

Is it cliche to tell a story about Italians that involves wine, extortion, and murder? Maybe. Is it about to happen? Definitely.

At the end of the 19th century and into the early 20th century, there was a large influx of Italian immigrants to the city. Many settled in the lower French Quarter.

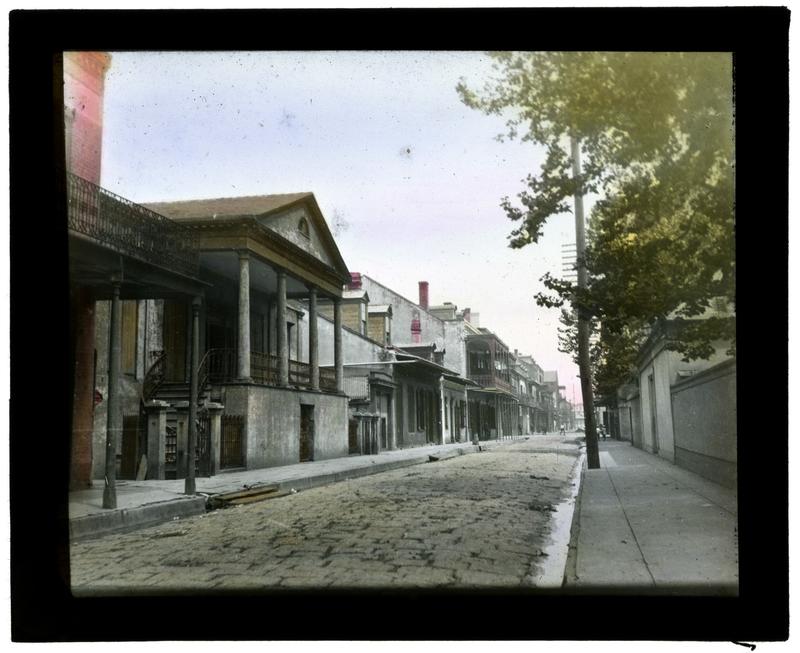

Rosanna Shephard is a docent at the Beauregard-Keyes House in the French Quarter, which was built in 1826 and has a long history. It was the home to a Confederate General (Beauregard) and an American author (Keyes). But this isn’t about the French, or the Civil War, or literature; it’s about some Sicilians: The Giaconas.

Even though it’s called the French Quarter, Shephard says this area was called Piccolo Palermo during that time, because it was like a little Sicily. “They were poor, and many didn’t speak English, so they tended to stick together, it was a closed community.”

The Giaconas came with the first migration of Italians to New Orleans, a group of prosperous merchants who made their fortunes on Decatur Street in the 1870s and ‘80s. Pietro and his son Corrado Giacona ran a successful wine business in Italy. They made a profit, and so were bothered by the Mafia (and the police) who all wanted a piece of the pie. So they left. This is why a lot of the wealthy came to America—to get away from all of the turmoil and violence that was going on in Palermo at the time.

After a few years in New Orleans, Pietro and Corrado were ready to get back into the wine business. This lead them to the Beauregard-Keyes House: it was cheap, since the neighborhood was falling apart, and there was a cool basement to store the wine, an uncommon feature for a New Orleans home.

Rosanna Shephard in the basement of the Beauregard-Keyes House, standing in front of the wine cabinets her grandfather and great-grandfather used to store the wine they produced and imported for their business.

CREDIT LAINE KAPLAN-LEVENSON / WWNO

Shephard loves to give tours and spend time at the Beauregard-Keyes House—it’s her history. She’s the granddaughter of Corrado Giacona, and her own father grew up in the house until he was 15. So it may not be called the Beauregard-Giacona House, but Rosanna keeps the family name alive and well inside those walls. And it’s there that Pietro and Corrado opened Giacona and Company Wholesale Liquor Dealers.

An original receipt from Pietro and Corrado Giacona’s wine company, stored at the Beauregard-Keyes House

CREDIT LAINE KAPLAN-LEVENSON / WWNO

From the end of the Civil War up until World War I, a lot of Sicilians came to Louisiana, and it happened fast. In 1882, there were fewer than 3,000 Italians in the state. Thirty years later, there were 45,000. This spike happened with the second wave, which brought the lower class. Poor Sicilian peasants began arriving by the thousands in the late 1880s to harvest sugarcane.

Justin Nystrom, assistant professor of history at Loyola University, says these poor migrants brought “some of the bad things from Sicily, like the criminal activity, particularly extortion,” that the merchants were so happy to get away from. This is why the wealthier immigrant group wasn’t exactly welcoming to this incoming migrant class. Turns out, mobsters are immigrants too. And although these mobsters had no godfather and no organized plan, they did have a name: The Black Hand.

The Black Hand were a group of thugs who would write extortion letters, stamped with a black hand, demanding a percentage of business profits, or else the recipient would meet an untimely death, or their business would be bombed.

The Giaconas were being extorted by the Black Hand. In this case, men were coming in from rural Louisiana for the company wine but not paying for it. And then, on June 16, 1908, around 9:30 p.m., Nystrom says four men showed up to do just that.

“At some point Pietro Giacona decides he needs to take a stand against this, and he invites them in to have dinner and talk about business.” Everyone’s in the dining room, they’ve been drinking, and they’ve stripped to their undershirts. They start arguing, and there are demands for Corrado and Pietro to give them money. “So Pietro says ‘OK, I’ll get the money,’ but instead he returns with a brand new rifle and opens fire on these guys.”

Three of the men die on the spot. One escapes but is found a few blocks away, lying beneath a nearby shed, pressing a dead chicken to his wound in an attempt to stop the bleeding from a rifle shot through his lung. Nystrom continues. “His son grabs a pistol from a nearby table and later he says, ‘I was a mad man. I don’t even know if I emptied my pistol or not.’”

The Black Hand arrived that evening unarmed, expecting their scare tactics alone would do the trick. Because seriously, who shoots up the Mob? Pietro and Corrado were arrested the next day but were eventually found innocent—and celebrated as local heroes by the Sicilian community.

New Orleans Item, June 17, 1908. This issue includes a cartoon that depicts the murders that took place the night before at the Beauregard-Keyes House.

CREDIT THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION

Nystrom says it was an important moment for this Black Hand, “because after that, that kind of activity dies down. The conflict between the Giaconas and these criminals is really a classic case of class conflict. It’s an Americanization story that takes place in lots of cities in lots of contexts. But basically the Giaconas were saying there were certain things that were OK from the old country, but this sort of extortion was not one of them.”

Though because it was said with guns, the family lived in fear of retaliation for years following the incident. Rosanna Shephard felt this firsthand.

“The men in the family refuse to talk about it and would not let anyone else talk about it in front of them,” she says. “So the only info we got was from the women, because they were the only ones who talked. And when I would ask my father, he would turn at me and say, ‘you will never speak of this again,’ because there was still fear of repercussions, of retaliations. So we were protected as children, because you never felt safe.”

So the drama really did last generations, and so did the prejudice from non-Italians that were fueled by these rivalries, says Shephard. “When my mother was going to marry my father, she was French and Irish. Her family wanted to disown her, because she was marrying a dirty Italian.”

What did her father end up doing professionally? He managed the One Two Three Bar across from the Roosevelt Hotel. “Yeah, you know, even though he didn’t produce wine, he served it. That was his way of paying homage to his heritage.”

Shephard recently received proof that this rivalry is finally in the past.

“A family of one of the victims of my grandfather was on a tour here recently, and they were told about me working here, and they thought it was a great idea to meet me. I don’t think that they hold a grudge!”

She says, at this point, it’s just a good story.

TriPod is a production of WWNO—New Orleans Public Radio, in collaboration with the Historic New Orleans Collection and the University of New Orleans Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies. Special thanks to Evan Christopher for the theme music.

Catch TriPod on the air Thursdays at 8:30 a.m. and Monday afternoons on All Things Considered.