The Women Who Fought For And Against The ERA: Part I

This is the first in a two-part series on the local second-wave feminist movement and the battle over the Equal Rights Amendment. Listen to Part II here.

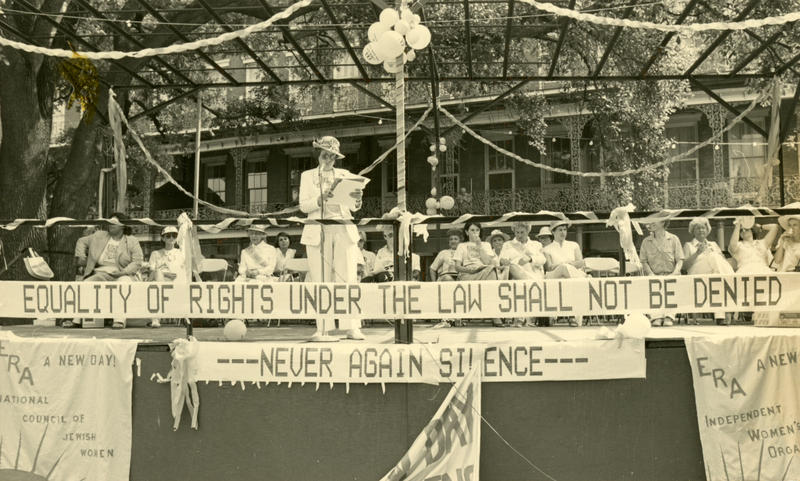

It’s July 3rd, 1982. Feminists are marching through downtown New Orleans in support of the Equal Rights Amendment, the ERA.

WDSU covered this march at the time: Under a scalding afternoon sun, several hundred ERA supporters wound their way from Armstrong Park through the CBD and headed for Jackson Square and a round of speeches with the theme: a new day for the ERA.

This march was also a jazz funeral, but it wasn’t for a person. It was for the Equal Rights Amendment.

Women marching in the French quarter: Pat Denton, Betty Godso, Sally Lunt, Kathy Wilson, ERA March and Jazz Funeral, New Orleans, 1982

CREDIT PAT DENTON COLLECTION / NEWCOMB ARCHIVES, TULANE UNIVERSITY.

According to WDSU: They decided on a jazz funeral, not to bury the idea, but to praise it. The traditional jazz funeral, they say, starts out in sadness but builds to happiness with the thought of new life. So too, with this jazz funeral.

The Equal Rights Amendment had just fallen three states short of being ratified, but these women came out to show they weren’t going to stop fighting for the ERA.

So what exactly was the ERA? Clay Latimer, a New Orleans lawyer, activist, and member of the women’s movement, can still recite it by heart.

“Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex. That was the whole language of paragraph one.” Clay said she honesty can’t remember if she was at that march. It was over 30 years ago. She did remember that there was a jazz funeral mourning the ERA after it wasn’t ratified. And decades later, scholars are still studying why.

Text of the Equal Rights Amendment

CREDIT PAT DENTON COLLECTION / NEWCOMB ARCHIVES, TULANE UNIVERSITY

“By the way, most people do not know that,” says Janet Allured, a professor at McNeese University in Lake Charles and the author of Remapping Second-Wave Feminism: The Long Women’s Rights Movement in Louisiana. She said, “If I ask my students this, they don’t know that the Equal Rights Amendment is not part of the Constitution. It never passed. It was never ratified.”

Spoiler alert. Except, not really, because that’s not what this story is about. What’s interesting about the fight over the ERA is not that it never happened, but that it really looked like it was going to happen, until it didn’t. In the 70s and 80s, there were a lot of different feminist groups in New Orleans that were local chapters of national organizations like the National Organization for Women or NOW. Clay joined NOW on August 26th, 1972.

NOW was co-founded by Betty Friedan in 1966. If Susan B. Anthony is the poster child of first-wave feminism (the right to vote and all that), then Betty Friedan is the poster child for what we call second-wave feminism. This brings me to the lavender top Clay was wearing the day I interviewed her in her apartment. I wouldn’t have noticed it, except for something Clay said. “In the early days of the women’s movement, Betty Friedan labeled the lesbians, especially lesbians in the National Organization for Women, as the lavender menace.”

Friedan rescinded this label later on but was homophobic in the beginning of her career. She called lesbians the lavender menace, warning NOW chapters across the country not to organize with them. She said they would be a detriment to the cause. “And lesbians picked it up as a as a symbol of pride,” Clay said.

So I asked her, “you’re wearing lavender today. Is that a coincidence?”

“No,” she said. “I’ve tried to buy lavender clothes when I can find ones that I like.”

I like to think about Clay in a department store holding a lavender shirt out at arm’s length, admiring it, and tossing it into her shopping cart with a little smile on her face, sticking it to Betty Friedan. But Friedan was not alone in this sentiment. Second-wave feminism, like all movements, was internally divided, often along lines that corresponded to individual identity—from race to politics to sexuality. The New Orleans movement was led mostly by queer women, which wasn’t the case for the statewide movement, or the nationwide movement.

Members of the Louisiana Lesbian and Gay Political Action Caucus, Laura Peebles, Leonard Doty, Cliff Howard, Alan Robinson, at ERA March and Jazz Funeral, New Orleans, 1982

CREDIT PAT DENTON COLLECTION / NEWCOMB ARCHIVES, TULANE UNIVERSITY

Janet Allured wrote about why queer people were more prone to organize, and why married women held back.

“We’re sort of a poorer state, and we are a more reactionary state,” she said. “And it’s just more difficult for women who are married to men to risk that by joining a feminist movement that probably was not very popular. And not only would that be difficult for them in terms of social ostracism and their profile in New Orleans, there would also be concern that it would hurt their husband’s career.”

But there were married straight women in the local movement, such as Louadrian Reed. Louadrian grew up in New Orleans and lives in Broadmoor. She was the first African American to join the Independent Women’s Organization, the IWO.

“And I’m still a member,” she said, “because the organization is still intact.”

In addition to the IWO and NOW, there was also the WLC, which stands for the Women’s Liberation Coalition. NOW and IWO were considered liberal groups, whereas the WLC was the more radical collective. The bra-burning stuff, that was the WLC. These local feminist chapters usually didn’t work together. They had different ideologies about how to organize and what to fight for, but they all came together to support the ERA.

And Louadrian Reed had her family’s support. “To tell you the truth, my husband backed me. Often he went up to Baton Rouge with me. Maybe because he was a black man and he had seen it on another side, I don’t know, but he thought it was fair and he came along with us.”

Her husband is deceased, but Louadrian said he may have considered himself a feminist. “And he had two sisters and three girls,” she adds. “So you know what I think, even about some politics today: It doesn’t bother you until it hits home.”

This is why Louadrian was surprised to find that her strongest opponents, those against the ERA, were women.

“Some of the biggest opponents of the Equal Rights Amendment, the people who showed up when it was coming up in the Louisiana State Legislature were majority female,” Janet Allured said. “Why would that be the case? Well there’s a lot of different reasons for that. Those were women who had invested in a certain way of life, and their lives might have been, or they were afraid that they might have been, radically changed by women’s equality. And those people absolutely were housewives, generally who didn’t have careers and who were very concerned that the Equal Rights Amendment was going to change the cushy arrangement that they had at that time, right? Where they stayed home and took care of children, and their husband went out to work.”

Doonesbury Comic, 1982

CREDIT G.B. TRUDEAU / PAT DENTON COLLECTION, NEWCOMB ARCHIVES, TULANE UNIVERSITY

Interestingly though, the leaders of the opposition weren’t housewives. They were career women like Louise Johnson, one of just two women in the Louisiana House of Representatives in 1972. She was a Baptist from Northern Louisiana. “You’re much more likely to see opposition coming from Baptists [in contrast to other Christian groups], but she was not a housewife,” said Janet. “She was an insurance agent, so she was actually a career woman. And so it’s kind of ironic that she would be leading the opposition to the Equal Rights Amendment in Baton Rouge in 1972.”

Still, Louise Johnson connected with conservative housewives through a group called Females Opposed to Equality, or FOE. When asked why she didn’t support the ERA, Johnson said, “there are only three groups that stand to profit by passage of this amendment—the prostitutes, the homosexuals, and the lesbians.” Meaning, if you weren’t one of those three things, you shouldn’t be voting for this, said Janet.

“Politics of respectability is what we call that,” Janet said. “If they wanted to maintain a kind of respectable image or social status, they didn’t want to be tarred with those feathers.”

Clay Latimer said she watched as this message started to influence opinion. She would go up to Baton Rouge to lobby for the ERA and talk to male opponents of the amendment. “Many of them said their wives were opposed to it, and that’s why they had to vote against it.”

Louise Johnson.

CREDIT LOUISE JOHNSON COLLECTION, M-134, BOX 2, FOLDER 1, SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, MANUSCRIPTS, AND ARCHIVES, PRESCOTT MEMORIAL LIBRARY, / LOUISIANA TECH UNIVERSITY, RUSTON, LOUISIANA

Who knows if those men were telling the truth, but there’s no doubt Louise Johnson’s strategy was working.

And the mastermind behind the national campaign, the most prominent ERA opponent, was a woman from Illinois named Phyllis Schlafly. Schlafly spoke on NBC in the 1970s on a late-night talk show called Tomorrow with Tom Snyder saying, “the equal rights amendment will take away the right of a wife to be supported by her husband in a home provided by her husband and the right to have her husband support her minor children.”

Schlafly died in 2016 but not before endorsing Donald Trump for President, which isn’t surprising because she was known for being a conservative activist and the founder of the Eagle Forum, a conservative pro-family interest group.

In a later interview with online storytelling platform Makers, Phyllis sums up where the ERA was headed when she came onto the scene in 1972. Things were looking good for the ERA, and Phyllis was swimming upriver. “Everybody who was anybody was for the ERA. All the prominent politicians from Ted Kennedy to George Wallace. Three presidents: Nixon, Ford, Carter.”

Phyllis Schlafly with Ronald Reagan, March 25th, 1987

CREDIT PHOTOGRAPH C39751-?, WHITE HOUSE PHOTOGRAPHIC OFFICE: 1981-89 COLLECTION / THE RONALD REAGAN PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

The amendment had been overwhelmingly passed by Congress and then went to the states for ratification, but that was before Phyllis Schlafly, who had a master’s in political science from Harvard. She ran for Congress in the 50s but lost. After that didn’t work out, she went to writing. Phyllis self-published a conservative book called A Choice, Not An Echo, which urged conservatives to rally against liberals. She sold three million copies out of her living room. With this attention garnered, she set her sights on the ERA and taking it down.

“They definitely underestimated me,” she said. “They did not believe I could win.”

More on Phyllis Schlafly and the death of the ERA in Part II of this series.

TriPod is a production of WWNO—New Orleans Public Radio, in collaboration with the Historic New Orleans Collection and the University of New Orleans Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies.