The Secret Basketball Game That Desegregated Louisiana High School Sports

TriPod New Orleans at 300 revisits the first integrated high school sports contest in Louisiana on February 25, 1965.

It’s the last practice of the season for the Jesuit High School basketball team. They run in blue and white shirts up and down the court.

“We played it at the Jesuit gym, right there on Carrollton Avenue,” says Harold Sylvester, remembering what it was like walking into that gym for the first—and only—time.

“There was a big disparity in facilities. We didn’t have a gym. We didn’t have lockers, we didn’t have a shower. And so, walking into that gym for the first time was like, wow, what is this?”

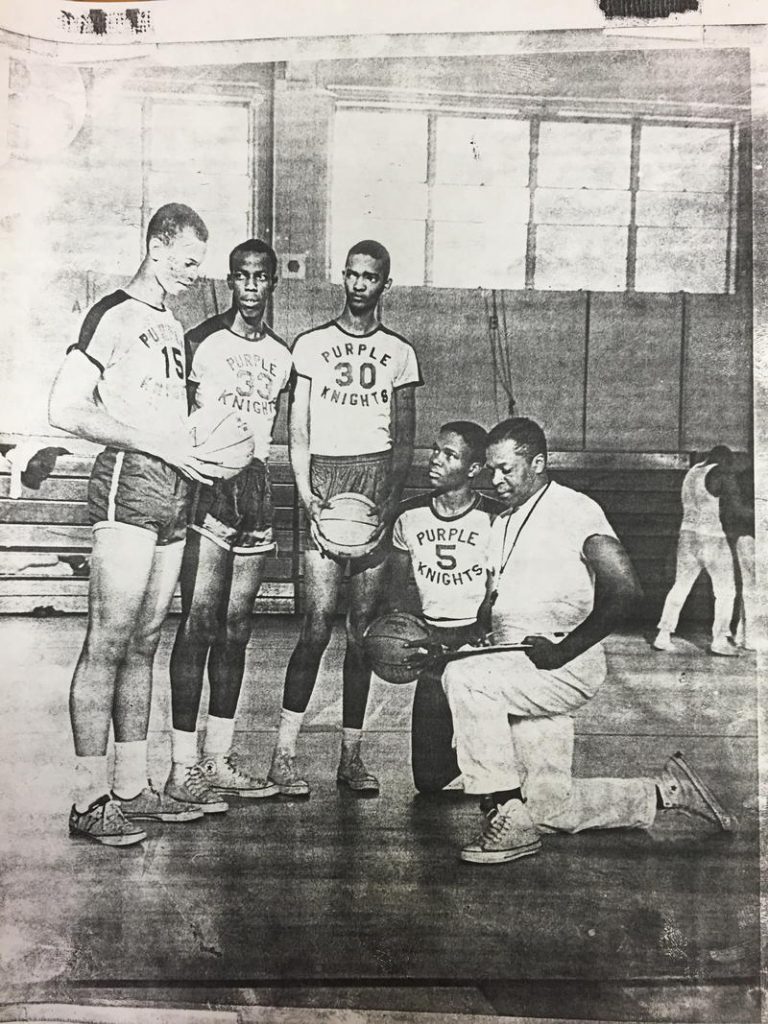

Sylvester was a star of his team, but it wasn’t Jesuit. He was a Purple Knight for St. Augustine High School, or St. Aug.

Harold Sylvester (right) with a St. Augustine Purple Knight teammate

CREDIT HAROLD SYLVESTER / AMISTAD RESEARCH CENTER

“Harold was younger. He may have been a sophomore when we played that game,” says Glenn Goodier, who played for Jesuit. “He was a very, very good player as a sophomore.”

Goodier is now a partner at the Jones Walker law firm and has been there practically since he graduated from college. He’s lived in New Orleans his whole life and grew up in the Bayou St. John neighborhood on Taft Place. He went to Holy Rosary grammar school, and then on to Jesuit, a private Catholic school. Sylvester’s St. Aug was private and Catholic too, one of only two black private schools in the city. He grew up in the adjacent Calliope housing projects, which have now become the Benjamin C. Cooper homes.

“So, it was that kind of upbringing,” he says.

Both guys were playing ball in 1965, just when New Orleans private schools desegregated, but the city’s high school sports leagues were still segregated. That’s despite the National Basketball Association integrating several years before. So Jesuit didn’t play St. Aug. But they were the two top teams in the city. Efforts to integrate the leagues, including lawsuits, had failed.

“What I learned later on was that the president of Jesuit High School got together with the president of St. Aug, and they wanted to show the Louisiana High School Athletic Association that black and white teams could play one another without there being any problems involved,” remembers Goodier.

The coaches worked behind the scenes to pair the two teams against each other. They decided on a secret match on Jesuit turf. But Sylvester says the motive wasn’t explained to the players at the time.

“My memory is that we were in the locker room,” he says. “Coach Nick Conner came in and said, ‘We’re going to play Jesuit.’”

And the talk started.

“We had not seen any of the players, but they sounded like gods, you know the way they were written up in the newspaper. If you read the Louisiana Weekly or read about us in The Times-Picayune, you know, the articles are very short and terse, and they just had, you know, St Aug beat Lincoln or Landry, one of the other black schools, and then they would give you the score, and that was it. You know, totally devoid of personality. So, we thought we knew them the same way you’d know Bill Russell from Sports Illustrated. So, we were going in to meet the gods—and try to beat them.”

What’s interesting is that, up until this point in the story, Goodier and Sylvester remember things almost identically. But after hearing the announcement about the game from their respective coaches, their memories and experiences of this shared moment stray. Goodier remembers hearing this news and not thinking much of it.

“To us, the coach said we were gonna play, so we put on our shoes and tied them and played. It didn’t matter to us—we knew it was a scrimmage, so it wasn’t like we were playing for something that really counted.”

To Goodier, this was just another thing his coach was asking him to do. And it wasn’t part of the official season. But for Sylvester and his team, it counted.

The two men also had very different experiences sharing this news with their parents. Goodier says, again, it was a non-issue.

“I can’t remember any discussion with my mother. I probably said ‘look, we’re gonna have this scrimmage with St. Aug,’ and she said, ‘oh, that’s fine.’”

Not so simple with St. Aug. Many parents saw playing Jesuit as something that could put their children in danger. And they had reason.

“That same year we went up to Bogalusa, and we had a new priest from the north who came down and wanted to stop for some pie,” remembers Sylvester. “We tried to tell him that we couldn’t stop in that place, but he really didn’t understand. And I’m letting something out of the bag because I never really even had this conversation with my parents, but there were four of us that went into that restaurant, and they just ignored us. But the next thing we know, trucks started pulling up to the front of the restaurant, and the guys literally came in and dragged us out and took us to the back of the building. And this indelible memory is the shotgun that got pressed to my forehead. So, that happened. And so now, two months later, three months later, we have a proposition about going into Jesuit knowing what can happen and what often happened at that time.”

It’s understandable that Sylvester’s parents wouldn’t want to put him in that position of being a target again. But that was the difference between these Purple Knights and their families.

“My dad, he—and this gets, uh, sometimes very tough—but he was an activist in his own way. Having endured in World War II and essentially having to spend all of WWII below deck, because the black people were, you know, essentially service people in many of the arenas, while they were trying to fight for freedom, for America, who would not grant them their freedom. When the next generation comes along saying, ‘why do you take that? Because we won’t, and please understand that we won’t.’ My dad was a barber, and I had an Afro. Which was a very strange dynamic. You know, why won’t the barber’s son get a haircut?”

Members of the Jesuit team today. From left, Ronnie Britsch, Tommy Morel, John Carrere, Billy Fitzgerald, Glenn Goodier, Joe Williamson, Art Hamburger and Drew Gates

CREDIT JESUIT HIGH SCHOOL OF NEW ORLEANS

Some players on both teams were barred by their parents from playing, but most did, including Sylvester and Goodier. They paint different pictures of game day. Goodier says families weren’t in the stands.

“No one in the stands at all, the gym was locked, so the only people there were coaches, but other than that no parents, no anyone else,” he says.

Sylvester remembers a limited audience. And they remember the outcome differently.

Goodier says there was no clock kept for score and five untimed quarters.

“We actually beat them by 22 points,” Sylvester says, laughing.

“Well, we had our two starting guards missing—our two best weren’t there,” Goodier adds. “Not that that should mean anything, but it wasn’t like, ‘gosh, we need to win,’ or ‘we’re sorry we lost.’ It was just kids playing basketball.”

Harold Sylvester poses with trophy and Bishop Harold R. Perry, the first African-American bishop in the 20th Century.

CREDIT HAROLD SYLVESTER / AMISTAD RESEARCH CENTER

The game was on February 25, 1965, which is another curiosity, Sylvester says.

“Here we are playing what is the first integrated sports contest in the history of the state of Louisiana, on a Friday,” he says. “Malcolm X was assassinated that Monday before. So there was a whole ‘nother reality going on everywhere else, and we’re just getting around to playing an interracial basketball game.”

And there’s a victorious moment when the Purple Knights win, yet it must have been awkward, too. “Right,” Sylvester affirms.

“It was how fast can we get out of here so that we can celebrate,” he says, “because you couldn’t in that room.”

And no bragging rights around town. The game stayed a secret for a few months before the coaches told the papers. And that was the beginning of desegregating local high school sports.

By 1967 when the leagues were fully integrated, Sylvester and Goodier were playing in college—Goodier for Loyola, Sylvester for Tulane. He went on to a life in Hollywood, and made a movie about the game called Passing Glory.

“When I was writing the film, I had to reflect on how far we had not advanced, you know, from 1965,” he says. “How, a lot of things were, superficially, very different, but fundamentally a lot of things remained the same in 1992. And then I watched the film again this morning, and I think you could make the leap back 50 years and say that substantially, significantly, we’re in the same place that we were in 1965. And that is a huge disappointment.”

TriPod is a production of WWNO—New Orleans Public Radio, in collaboration with the Historic New Orleans Collection and the University of New Orleans Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies.

Catch TriPod on the air Thursdays at 8:30 a.m. and Monday afternoons on All Things Considered, and subscribe to the podcast on iTunes to get all the latest episodes delivered to you on the go.