The Second Battle Of New Orleans

TriPod: New Orleans at 300 returns with a two-part series on highways. The first looks at a controversy so intense, it’s called the Second Battle of New Orleans.

Mark Souther is an associate professor of history at Cleveland State University. He’s in the French Quarter at Washington Artillery Park, sitting on top of those big steps between Jackson Square and the Mississippi River.

“They wanted to run this Riverfront Expressway from the Pontchartrain Expressway, which is in the Central Business District, along the riverfront, and then over my back down toward the Marigny,” says Souther. And then turn it back northward and connect back into I-10. And so you would have the French Quarter encircled by freeways, one of which was actually going to block the view between the river and Jackson Square…”

…where he’s sitting right now, and where he wouldn’t be sitting right now, if master of highways Robert Moses had had his way. Let’s back up to 1946. World War II is over, and America is going crazy over cars.

Pamphlet showing the San Francisco Embarcadero Expressway and the proposed New Orleans Riverfront Expressway

CREDIT THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION, GIFT OF MR. RICHARD O. BAUMBACH JR. AND MR. WILLIAM E. BORAH, [84-102- L.2]

This is what many city leaders wanted at the time—traffic plans to move people around the city really quickly. Don’t worry, they said, these freeways won’t affect neighborhoods. “Of course, it’s well known that freeways ended up doing quite the opposite,” Souther says. “But, in New Orleans, it was unusual in that Moses proposed running a freeway right through an area that was starting to have a group of New Orleanians, at least, who valued it.”

The French Quarter.

At the start of the 20th century, the city seemed less invested in the old and decaying French Quarter and more interested in developing an adjacent downtown. But during the First and Second World Wars, people weren’t vacationing in Europe much (as one can imagine), so the tourism industry in New Orleans saw its first opportunity to market the quarter as the “closest you can get to Paris, without having to go to Paris.”

This is what also started to drive preservation interests. The idea was, “hey, we have an old and romantic city right on our doorstep, but we kinda let it go…so let’s fix it, so people come, and like it, and come back.”

That love of the Quarter only grew in the decade after Robert Moses’ plan was announced. But, in 1958, the Louisiana Department of Transportation decided: We are doing this Riverfront Expressway.

“In fact, even the promoters of the freeway amazingly tried to make these feeble arguments that motorists who are cruising along at 60 or 70 miles an hour over this 40 foot high elevated stretch of freeway could admire the rooftops of the French Quarter as they passed by,” says Souther. “It’s like, ‘the French Quarter will look far better from the sky!’ Surely they didn’t even believe their own words, and no one else did either. But, they were saying these things.”

Whereas highway opponents were calling it the Berlin Wall. And then someone named the controversy the Second Battle of New Orleans. That was lawyer William E. Borah. “It’s called a battle because it was ferocious, and there were fights,” Borah says while giving a talk at the 2016 Historic New Orleans Collection’s WRC Symposium. “People didn’t want to go out in public; families were split. I mean, it was horrendous, horrendous.”

Borah was born in New Orleans, got a law degree, and then went to London to get a master’s in economics. He came home for a visit and was having a drink with his friend, another lawyer, Richard Baumbach.

“And I said, ‘well how are things going?’ He said, ‘Well Bill, we’re worried about this expressway.’ I said, ‘what’s an expressway?’ He said, ‘well, Bill, it’s a big highway, and they’re going to put it in front of Jackson Square, and they’re going to run all of the roads through the French Quarter.’ And Dick and I looked at each other and we said, ‘that’s crazy.’ And we said, ‘why don’t we go down to the Chamber of Commerce and see why these guys are doing this?’”

New Orleans, Vicinity of Pontchartrain Expressway

CREDIT THE CHARLES L. FRANCK STUDIO COLLECTION AT THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION, [1979.325.6488]

“It had the backing of the mayor. It had the backing of the city council, it had the backing of the planning commission, it had the backing of the governor. Hale Boggs, congressman, loved it. Senators—everyone who ordered this highway, they looked around and said, ‘look at what the rest of America is doing. They’re building these freeways and we don’t have one. We gotta have one.’ Again, it’s this New Orleans thing. It’s like, ‘we have to be like these other cities,’ when we are extraordinarily different. We are different! And that difference is our strength, not our weakness.”

He and his fellow opponents launched a citywide grassroots campaign, posting banners and plastering the city with 400,000 flyers.

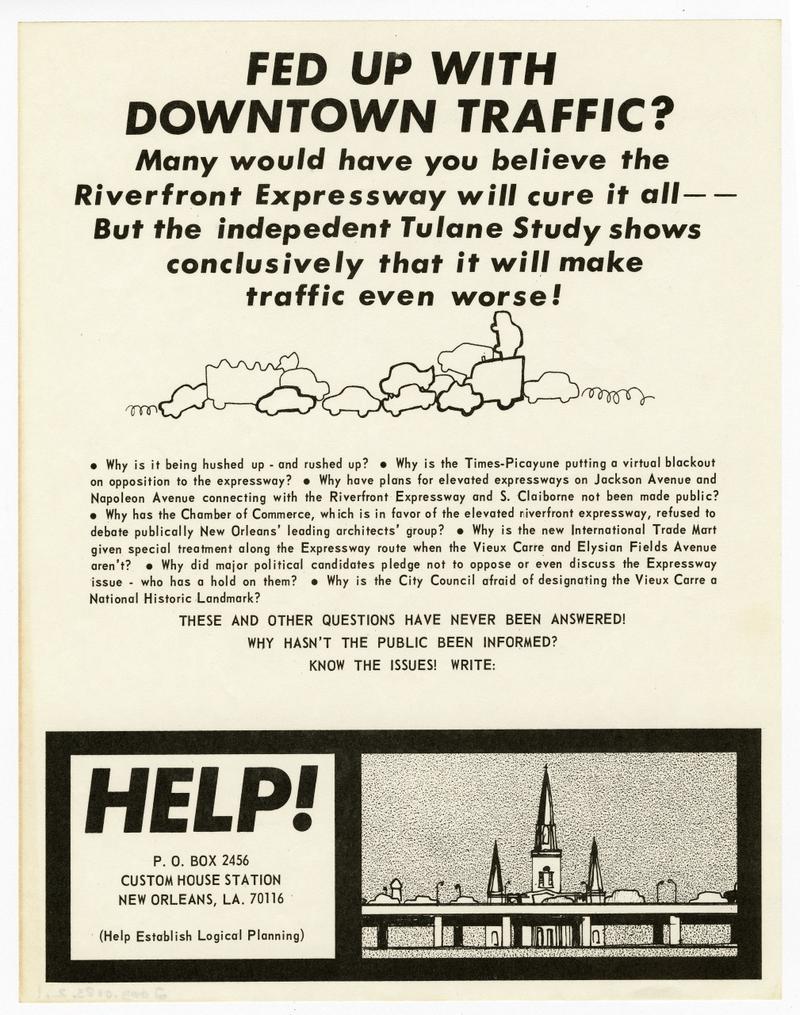

One of the flyers Bill Borah and HELP handed out all over the city, Octopus eye-view of the New Orleans-to-be.

CREDIT THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION, GIFT OF MR. RICHARD O. BAUMBACH JR. AND MR. WILLIAM E. BORAH, ACC. NO. 84-102- L.1

“We knew who was proposing this highway. A lot of their children were working with us. We would get their daughters to hand their fathers flyers on their way to work downtown, okay?”

But there were roadblocks, Borah says, such as the local press.

“If I said the Times-Picayune wanted this highway built in the worst way, you could not get a letter to the editor published in the Times-Picayune opposing this facility, or The State’s Item. If you held a press conference, they wouldn’t cover it.”

They did have support from the little Quarter paper, the Vieux Carré Courier. But it only published once every two weeks. That wasn’t enough, so Borah and his constituents formed an organization called Help Establish Logical Planning, or HELP. The group was made up of Vieux Carré property and business owners and landmark preservationists alongside Borah, such as the late Martha Robinson.

The problem was, the city and state were both all about that highway happening. The only way to bring it down was to make it a nationwide cause.

“The nation had to get upset,” Borah says. “The thesis was Jackson Square and the Vieux Carré is a national registered historic district. It belongs not just to the people in New Orleans and Louisiana, it belongs to America, and America has to stop it.”

In 1967, almost 20 years after Robert Moses came to town, Borah and his partner Richard Baumbach wrote a history of the expressway battle and published it in the Courier, titling the summary The Second Battle of New Orleans. Hodding Carter, the Pulitzer prize-winning editor of the Delta Democrat Times, in Greenville, Mississippi, wrote a cover letter and sent it along with the summary to more than 200 newspapers across the country.

“And then, sure enough, newspaper articles started coming up from Mobile, not just Mobile, but Nebraska and Alaska, and Providence, Rhode Island, opposing this highway,” Borah exclaims. “Because everybody in the country knew about the French Quarter, and an amazing amount of people had a tie to it somehow. I mean, United States senators stood up on the floor to criticize this highway in the Senate!”

Borah and Baumbach looked at all the government documents on the expressway and concluded that there had never been a comprehensive study of possible alternative routes.

“I’m a young lawyer. At that time I had never practiced. I had trouble finding federal court! So I go to Washington with my dear friend Dick Baumbach to challenge this highway in federal court.”

The strategy was to exploit the fact that all these highway acts were brand new. So the idea was to find loopholes, reasons why it was actually illegal to go through with the elevated Riverfront Expressway, and then go to the new and still figuring-itself-out Department of Transportation, and say, as Borah says it:

“You build this highway, and if you haven’t done the following things before you build it, you’re going to be in violation of federal law, and we’re going to take you to federal court, and we’re going to sue you, and we’re going to beat you.”

After many more meetings, reports, hours in court, and nasty coverage of the fight, the Second Battle of New Orleans ended in July 1969, when the Secretary of Transportation John Volpe canceled the project.

The view of Jackson Square from the viewing platform at Washington Artillery Park, uninterrupted by the Riverfront Expressway that was not built

CREDIT LAINE KAPLAN-LEVENSON / WWNO

The victory was the first one in the country after the 1956 Federal Highway Act was passed. He later remarked that his decision was “the beginning of a new tradition in the Department of Transportation regarding the nation’s heritage.” With that in mind, Borah wants to clear something up about an elevated interstate that was built and still stands.

“There’s a myth, a myth in this city, that when the highway was canceled, the roadway was moved over to Claiborne Avenue and destroyed that neighborhood. Wrong.”

Basically, the I-10 interstate over Claiborne Avenue in the Treme neighborhood didn’t happen instead of the Riverfront Expressway, it’s just that both were proposed at the same time, and both were supposed to happen. One didn’t, and one did. That story on the next TriPod.

TriPod is a production of WWNO—New Orleans Public Radio, in collaboration with the Historic New Orleans Collection and the University of New Orleans Midlo Center for New Orleans studies. Special thanks to Evan Christopher for the theme music.

Catch TriPod on the air Thursdays at 8:30 a.m. and Monday afternoons on All Things Considered. To hear this episode of TriPod again, subscribe to the podcast on iTunes.