The Monster: Claiborne Avenue Before And After The Interstate

TriPod: New Orleans at 300 returns with part two of its highway series. This is the story of the I-10 interstate bridge that sits above Claiborne Avenue.

Part one of this story was about the proposed Riverfront Expressway through the French Quarter and along the Mississippi River. That leg of the highway did not happen, and the French Quarter was saved from being demolished under a freeway. But that same year, 1968, a different section of the Riverfront Expressway did go up. Under that part? The Treme neighborhood, along Claiborne Avenue.

Dodie Smith-Simmons is a local civil rights activist. Walking along Claiborne today, with the freeway overhead, she describes what it used to look like. “Oak trees lined the neutral ground: businesses and homes, churches, so it was like a real neighborhood.”

Smith-Simmons points at what used to be the oyster house Lavada’s. “My classmates and I would put in and buy a loaf and divide it between four, five people, and you still had a nice sandwich.” Now, that property is a parking lot.

Dodie Smith-Simmons stands in the parking lot of what was Lavada’s, the oyster house on Claiborne Avenue she used to go to with her schoolmates.

CREDIT LAINE KAPLAN-LEVENSON / WWNO

To make the highway happen, the state had to acquire 155 individual properties along Claiborne between Tulane Avenue and St. Bernard Avenue. The state cleared more than 200 oak trees. In 1950, there were 123 businesses in this section, and almost 50 years later, just 44. One business that still stands, after a post-Katrina comeback, is the Circle Food Store. Smith-Simmons grew up in the 9th Ward, but like people all over New Orleans, her family still came to the Treme to make groceries.

“Anything you needed you could find at the Circle Food Store. Vendors would come in and sell their produce, their live chickens and turtles, and whatever. And I have not been in the Circle Food Store since it has reopened.”

She walks in.

“Wow, it didn’t look like this back then…oh this is wonderful.”

Being in Circle Food reminds Dodie of the other major reason her family came to this part of town.

“Back in the old days Zulu and the [Mardi Gras] Indians were not part of Mardi Gras. Or white Mardi Gras, I should say. It was a part of black Mardi Gras, and black Mardi Gras happened on Claiborne Avenue. We did not go to Canal Street,” or St. Charles Avenue, or pretty much anywhere else white people were celebrating. The freeway overhead was called the bridge.

Some referred to it as The Monster.

Snapshot view of Claiborne Ave. neutral ground before the construction of the I-10 overpass. Live oak trees shade a wide foot-worn path through the grass.

CREDIT THE WILLIAM RUSSELL JAZZ COLLECTION AT THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION, ACQUISITION MADE POSSIBLE BY THE CLARISSE CLAIBORNE GRIMA FUND, [92-48-L.47]

“There were people protesting the bridge being built in this neighborhood, but it was just the minority. This is white versus black, black versus white. And in the South, if you’re black, you’re not gonna win. So if this was something white folks want, that’s what they got.”

Louis Charbonnet is sitting around a table at Dooky Chase Restaurant in the Treme, with Lambert Boissier and Edgar Chase III, aka Lil’ Dooky. His parents, Leah and Dooky Jr. still run the business. “I was a young man at the time, and we were just shocked,” says Charbonnet.

“We had a funeral home on Dumaine and Claiborne,” adds Boissier. “My brother is over at Charbonnet [Funeral Home] now—we friendly competitors and in-laws. So it’s a family affair over here. And we not sure if we not kin otherwise!”

Boissier’s business closed some years after the interstate went up due to a fire. Charbonnet Funeral Home is still up and running.

“We’ve been in business since 1883,” says Charbonnet. “We’re the tenth oldest African-American funeral home in the country, and we survived that because we were half a block off of Claiborne.”

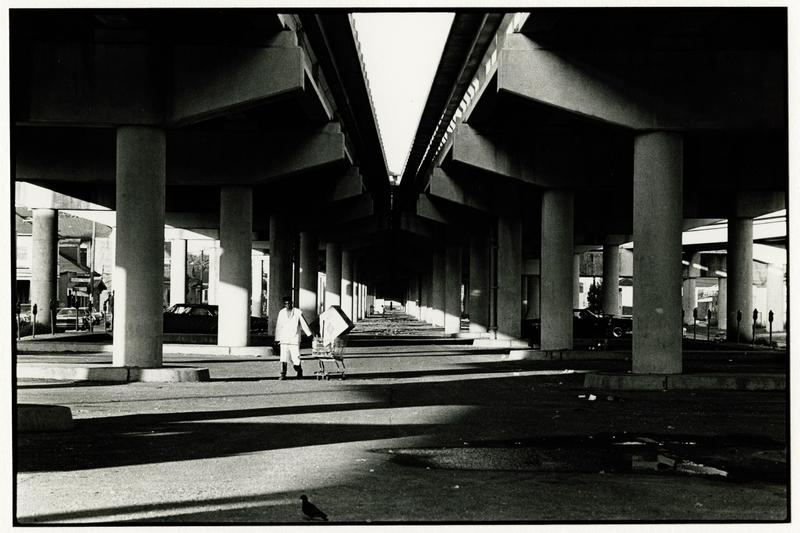

One of ten views of a jazz funeral on Claiborne Avenue. Rodney Batiste is seen as grand marshal in front of a car that would appear to carry the body. The brass band and second liners stand on either side of the street to allow the car to pass. The I-10 overpass looms overhead. Printed in 1993 from a ca. 1980 negative

CREDIT THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION, GIFT OF MR. CHRISTOPHER PORCHÉ WEST, [2004.120.3]

“There a lot of benevolent associations there,” Chase adds, “societies that helped people pay for things they couldn’t afford.”

Like Inseparable Friends, Charbonnet says. “There used to be all of these little society places that gave you money when you went to the hospital. The neighborhood fed on each other.”

He says what was a mecca of black-owned businesses was all of a sudden scattered around the city.

“New Orleans is a big city, but New Orleans is very colloquial. I could not survive if I were not in Treme. I couldn’t go in another section of the city and survive the way I’m surviving right now: because of the people, because of the culture, because of the type of people I serve, the Creole community that I serve. When you uproot something, it’s hard to plant it someplace else, and for it to survive.”

So there were all these business owners, and a strong, supportive community. Why couldn’t the project be stopped?

“We tried to organize some opposition to it, but it just wasn’t enough,” says Charbonnet.

It fell on deaf ears, he says. There were only two or three black people in local government.

The front page of a 1968 issue of the French Quarter publication the Vieux Carre Courier, showing a rendering of the I-10 interstate to be

CREDIT JOSEPH MAKKOS

Without that representation, “you got stuck with what came your way,” he says. “The interstate became a reality because of the haves and the have nots, and the have nots got stuck with the interstate.”

Within the system, there was essentially no one in government to defend the black community and communicate the cultural and economic necessity of keeping Claiborne intact. And outside the system, those who were active political organizers were busy with more pressing things.

Dodie Smith-Simmons was a member of the local chapter of the NAACP, and then CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality. She says the Claiborne interstate was not a focus.

“Because we were focusing on the five-and-dime store, their restaurants, then it was the Freedom Ride.”

In the mid ‘60s, they were working to end segregation, for the right to walk into any restaurant they wanted, go to any school they wanted, and feel safe no matter where they stood.

“Trees and flowers and grass were not our main interest at the time,” Charbonnet agrees. “We were worried about what was gonna happen to our children, to us!”

He says by the time they realized how bad the interstate would be for the neighborhood, it was too late. That caused the black community to organize in a new way.

It made them say: “This will never happen to us again.” Charbonnet says, as a result, “we’ve gotten blacks elected to positions that can represent the part we live in.” That includes Charbonnet himself, who was elected to city council in 1970, then as a state representative in 1972. Boissier was elected to city council in 1981, then went to state senate in 1999, and the constable’s office 2001, where he still works today.

Dooky Chase says, intentionally or not, racism was a factor in the interstate being built over Claiborne Ave.

From left: Edgar Dooky Chase III, Lambert Boissier, and Louis Charbonnet pose outside Dooky Chase’s on Orleans Avenue.

CREDIT LAINE KAPLAN-LEVENSON / WWNO

“People don’t know that they’re making decisions on race; it’s unconscious that they are,” he says. “But the power that they have tends to favor those who look like them. Power doesn’t flow to those who really need it, but it flows to those who are a certain color who already have the power.”

The idea of removing the interstate has been discussed since it went up and regained traction after Hurricane Katrina. Some people, including many Mardi Gras Indians, and Dodie Smith-Simmons, don’t think removing the interstate will bring back what once was and may even further gentrification throughout the Treme.

But others dream of seeing the day it comes down.

“It was a hot subject at the time, and it’s gonna be a hot subject continuously until that thing comes down,” Charbonnet says. Dooky imagines a future he hopes for. “When we’re both around, all three of us are around, 2026, we’ll be driving down Claiborne Avenue, historic with the treelines and the flowers and the azalea bushes. It would be our glorious two miles.”

TriPod is a production of WWNO New Orleans Public Radio in collaboration with the Historic New Orleans Collection and the University of New Orleans Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies. Special thanks to Evan Christopher for the opening theme music. Catch TriPod on the air Thursdays during Morning Edition and again on Mondays during All Things Considered. To hear TriPod anytime, anywhere, subscribe to the podcast on iTunes. TriPod’s also on Instagram and Twitter at @tripodnola. Thanks to Emma Long for research and production assistance this week.