The Legendary Lasties

TriPod: New Orleans at 300 returns with a new episode that spotlights a famous musical family, the Lasties. Host Laine Kaplan-Levenson sat down with drummers and cousins, Herlin Riley and Joe Lastie. This is the first in a series of episodes focusing on the rich history of New Orleans music. Listen to the full interview with Herlin Riley and Joe Lastie here.

Joe Lastie (left) and Herlin Riley (right) are drummers and first cousins. They sit in Herlin Riley’s music room in his home in New Orleans East.

CREDIT LAINE KAPLAN-LEVENSON / WWNO

“I was born in 1958,“ Lastie said. “We’re a year apart. I was born in 1957,” Riley added.

So they’re cousins, but they’ve got to have a relationship like siblings in a lot of ways, right?

“Oh yeah,” Lastie said.

Riley added, “Well, when we were growing up, we shared a bed together at some points and wet the bed on each other, that sort of stuff occasionally!”

Sibling stuff, you know? But back to music stuff: When you think about New Orleans music, you’ve got jazz, brass, rhythm and blues, funk, soul, gospel, and on and on. And you’re about to meet one family that’s all up in all of this music, a legendary musical family that Herlin and Joe are a part of: the Lasties. And according to Herlin and Joe, it all started at home, on Delery Street.

“1807 Delery Street in the Lower 9th Ward,” Lastie said.

“It was our grandparents’ house. And because it was our grandparents’ house, we spent a lot of time there,” Riley said.

And so did a lot of musicians who’d come by to jam with the Lasties. “People like Professor Longhair would come over to the house,” Riley said.

So imagine Joe and Herlin are toddlers, listening to folks like Professor Longhair (rhythm and blues) and Dr. John (funk), playing with their uncles Melvin, David, and Walter, who were known as The Lastie Brothers Combo (more R&B). Herlin’s mom, Betty, aka Miss B, was a well-known pianist and gospel singer (gospel), and jazz came from their grandfather, Frank Lastie. “And one of his first engagements was in the Waif’s Home in 1913 with Louis Armstrong,” Riley said.

Melvin Lastie, co; playing with the Chester Jones Band for Caldonia Club Advertisement. 1953, New Orleans, Louisiana

CREDIT HOGAN JAZZ ARCHIVE

It’s where Frank Lastie first learned to play music. The Colored Waif’s Home For Boys was a juvenile detention school on the outskirts of New Orleans. It’s also where Louis Armstrong was sent for two years after firing a pistol into the air on New Year’s Eve, 1912. These two boys together received their first formal music training. That’s one big reason why Herlin says his grandpa Frank was so steeped in the tradition of New Orleans music and the history of New Orleans music.

New Orleans Times-Democrat newspaper item, 2 January 1913. Noting arrests at New Year celebrations, including young Louis Armstrong. (Armstrong was sentenced to time in the Colored Waif’s Home, where he learned trumpet.) Times-Democrat, 2 January 1913

CREDIT STAFF OF THE TIMES-DEMOCRAT

Frank Lastie grand marshaled various brass bands in his lifetime (there’s the brass) and passed those traditions down to Herlin and Joe through his playing, through his stories, and by simply plopping the boys on a set of drums at three years old. But Herlin didn’t need real drums to play. His first drum set?

“The Quaker Oats grits’ box,” Riley said, “the grits and oatmeal boxes, because they were around, and they were made out of this hard cardboard. So when it was time to throw them away my grandmother would say, ‘throw this away, son.’ So I wouldn’t throw it away. I would take it between my legs and make a bongo out of it. It became a bongo.”

George Porter, Jr. and David Lastie band at Dorothy’s Medallion, New Orleans. View of a large woman, identified as Big Linda, wearing a fringed bikini and dancing in a cage. George Porter and David Lastie band are in the background playing on the stage while people sit at tables and drink.

CREDIT PHOTOGRAPH BY MICHAEL P. SMITH ©THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION

So Joe and Herlin are playing drums on oatmeal boxes, listening to their relatives play with the best musicians in the city, and without even trying, they’re just kind of…becoming musicians. Then, when they’re about to enter junior high school, Joe’s parents say the words he never wanted to hear: We’re moving. And not only are we moving, we’re moving to Long Island.

What went through Lastie’s head when his parents said they were moving? “I didn’t like it. I really did not like it,” Lastie said. “Me and my dad, we was getting into it, because my heart was in New Orleans. It wasn’t in New York.”

Joe was not happy. He knew he was destined to be a musician. He felt he was missing out, missing out on the people and the sounds he was so immersed in in New Orleans. So, up on Long Island, Joe figured out how to keep that music around.

“Look, let me tell you one thing about that, my dear. You know how you used to go to the library and check out books? Well, during that time I was checking out Pete Fountain, Al Hirt, and Preservation Hall.”

Remember those names.

“I was checking out that stuff so I could keep this music, this tradition in my head,” Lastie explained.

It’s amazing he had that desire and that commitment at 13 years old, and he did that for six years, until he finally convinced his parents to let him go back and finish high school in New Orleans. In 1976, Joe Lastie returned to 1807 Delery Street and graduated from George Washington Carver High School.

Lastie said, “and now, I don’t mean to jump. Do you know I wind up playing on stage with all three of them? Pete Fountain, Al Hirt, Preservation Hall?”

Delery Street was the musical home front for Joe and Herlin. Then there was the school marching band. Both Herlin and Joe studied with now-legendary music educator Yvone Busch at Carver High. You might not have heard of her, but in the world of New Orleans music, she’s a big deal. And, there was a third major element to their musical upbringing: the church.

“There was a certain groove, a certain kind of beat that they played in church.”

Herlin and Joe both played drums in the Guiding Star Spiritual Church on the corner of Derbigny and Vincent street in the 9th Ward. This is also where they learned, the hard way, that there was a difference between the music they could play at home and at church.

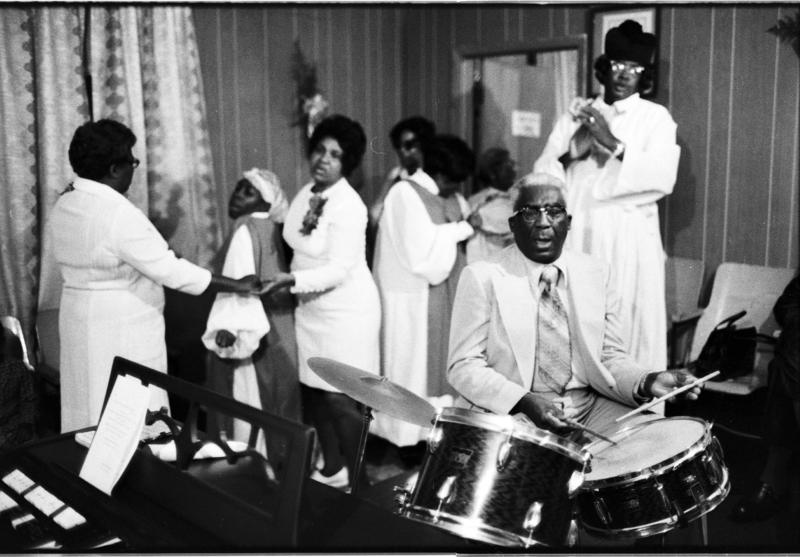

Guiding Star Spiritual Church, Deacon Frank Lastie on drums. View of a service inside the Guiding Star Spiritual Church that was located at 5900 N. Derbigny Street in the Lower 9th Ward neighborhood of New Orleans. Mr. Lastie is seen playng drums while congregants appear to dance in the background. One of the women is playing a tambourine and another claps.

CREDIT PHOTOGRAPH BY MICHAEL P. SMITH ©THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION

“When I was at home I was hearing James Brown and hearing all this other stuff. And I heard Cold Sweat,” Riley said. Soul music. And Riley loved hearing this soul music played at home, especially this James Brown tune, Cold Sweat. So he’d be playing drums in church, “and I’d try to to sneak a little Cold Sweat in there. My grandfather would say, ‘uh uh! Uh uh son, you don’t do that in here! You don’t do that here; you do that outside. When you playing in the church you playing church music—you keep it straight.’ And so I took it to heart.”

So what Riley plays in church is what he plays in church. Herlin and Joe both still play gospel music in their respective churches, but their childhood church, the Guiding Star Spiritual Church, ain’t dere no more.

“Katrina washed it away. So it’s somewhere in our memory now,” Riley said.

There are a lot of conversations about preserving New Orleans culture and music in particular, getting young people excited about musical instruments, brass bands, etc., so that these traditions live on. But what about the Lastie family? Herlin and Joe are in the same generation; they’re both around 60 years old. And some of the younger members of the family, their lives have been cut short.

Riley said, “it’s so unfortunate. I’ve lost two nephews who were actually musicians. As a matter of fact, I’ve just lost one of my nephews who played the tuba. He passed away September, this past September. And his brother played the trombone; he was killed in 2004. The police killed him.”

Police claimed Joseph Williams was trying to run them over with a stolen truck. He was unarmed when they shot and killed him, and no charges were brought against the officers. Joseph’s brother, Arian Macklin, died in September 2017 of poor health. These brothers were founding members of The Hot 8 Brass Band. Three generations after their great-grandfather Frank Lastie brought brass instruments out into the street, Hot 8 is an evolution of what their great grandfather started.

Hot 8 @ Young Men Olympian Jr 127th Annual Parade, New Orleans. 25 September 2011

CREDIT DEREK BRIDGES

Riley said, “the Hot 8 Brass Band also started at 1807 Delery Street in the lot. And we were looking for them to be the next generation of musicians to keep on the legacy, to keep the legacy up. Unfortunately they passed away,” Lastie added. And now it’s looking like no one’s passing the torch. But you never know, just have hope.”

I asked the cousins if there is a song that most ties them back to the Lasties. Riley said, “Ooh Poo Pah Doo. Ooh Poo Pah Doo ties me into the family because it’s my Uncle Jessie Hill who’s singing it, my grandmother’s brother. And he sings the song. My Uncle David Lastie plays the saxophone solo on it. As as matter of fact, Jessie Hill, who made Ooh Poo Pah Doo, is Trombone Shorty and James Andrew’s grandfather. And so we’re connected to them as well.”

Herlin and Joe are second cousins of Trombone Shorty and James Andrews. Forget Kevin Bacon, it’s all about six degrees of Lastie.

“We have a lot of wonderful memories being in the family. And I feel very fortunate growing up in a musical family, because the music has come to me so naturally. The spirit of the music has been a part of me all of my life, so even now I feel so at home when I’m at the drums. Even sometimes when I’m feeling bad, I can go to the drums and play music and feel healed,” Riley said.

Alright, this is kind of a joke question. I asked Riley about his last name and if he ever wished that his last name was Lastie. His response? Absolutely. Herlin’s dad married piano player and gospel singer Betty Lastie.

“My name is Riley, but a lot of the older musicians, when I was starting to come up, they’d actually call me Lastie. ‘Come here Little Lastie.’” And I took that with pride, because that’s the family legacy, the legacy of the family, the Lasties,” Riley explained.

“I’m wishing he would have changed his name earlier. Now,” Lastie joked.

I joked that Joe was going to start calling Herlin, Herlin Lastie. “I wouldn’t mind that,” Herlin replied.

Catch the full interview with Herlin Riley and Joe Lastie, on the TriPod podcast. TriPod is a production of WWNO in collaboration with the Historic New Orleans Collection and the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at UNO.