The Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case

It was June. It was hot. Kids were out of school, keeping busy outdoors. Parents were inside. It was kind of like how it is now, except it was 146 years ago.

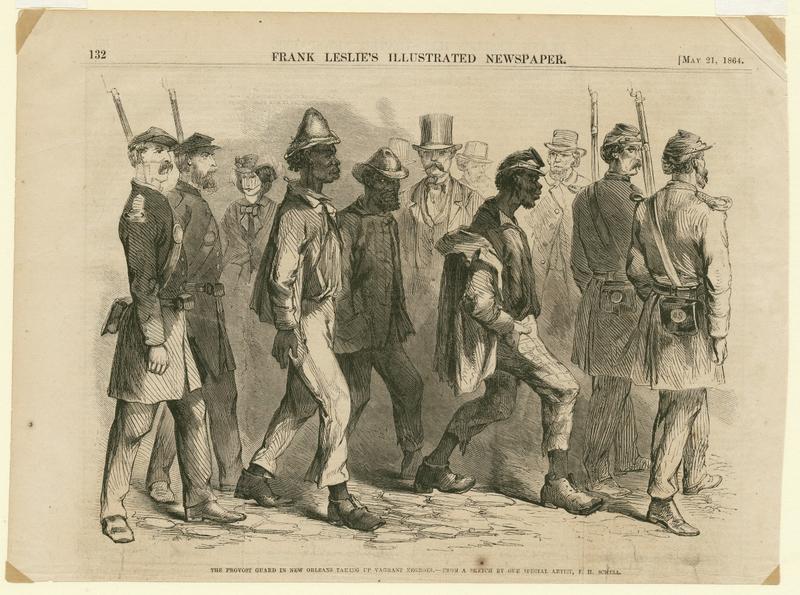

“It is a world turned upside down,” says Michael Ross, historian and author of ‘The Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case: Race, Law, and Justice in the Reconstruction Era.’ He’s talking about the year 1870, at the height of Reconstruction. “You have five cities in the South that have integrated their police forces, at a time when not a single police force in the North had integrated.

It’s true. The NOPD first hired black officers in the 1860s. New York City didn’t have an African American in their ranks until 1911. This is one of the many things that makes New Orleans a stage for social change in the United States after the Civil War. One crime in particular brought these changes into focus.

Molly Digby is 17 months old and playing outside with her older brother. Two women of color walk up to the kids and start talking to them, until they’re all interrupted by a loud noise down the street. The women tell the boy he can go see what all the excitement is about, and they’ll watch the baby. He runs off, and when he comes back, the women, and baby Molly, are gone.

“A white baby is abducted by two mixed race women called mulattoes at the time,” Ross explains. “That story would have been just one of many terrible stories of that day that would have been buried in the third page of the newspaper. But a number of factors lead to it getting front page attention.”

The press goes wild with this story. The city’s major papers are run by ex-Confederate Democrats. So they showcase the kidnapping as a direct consequence of racial equality, the message being even your toddlers playing on your own front lawn are no longer safe! For the city’s Republican leaders, there was a lot at stake; a baby was missing and the kidnappers needed to be apprehended. But the new status quo also needed defending from white supremacist critics. The pressure was on.

Henry Clay Warmoth is 28 years old, and he’s desperate to show that his police force could solve this crime. Warmoth is the Republican governor of Louisiana and needs to prove his government works, not only because he’s young, but a Northerner—one of the so-called carpetbaggers who settled in the South after the war.

“Henry Clay Warmoth put his best Afro Creole detective, Jean Batiste Jourdain, on the case,” says Ross. “And if they can have this black detective solve the Digby case, it will show the effectiveness of his integrated police force.”

It’s another example of how many sides had so much to prove here. Ross goes on.

“The Afro Creoles are this educated class of former free persons of color unique to the Gulf Coast in the Antebellum period, who are filling all the key roles in the Reconstruction government. The performance of men like Jourdain carries particular weight, because he’s essentially representing the race. The world is watching to see how he’ll do.”

The two female suspects Jourdain’s looking for are also Afro Creoles. There are lots of false alarms throughout the search, with people reporting they saw the baby. But then the police get a call that a white baby fitting Molly’s description was seen at a house on Camp and Bellecastle streets Uptown belonging to a woman named Ellen Follin. She and her sister Louisa Murray, who lived in Mobile, Alabama, ran an interesting operation known as a lying hospital, a place where white women who got pregnant in difficult circumstances out of wedlock went to escape the prying eyes of neighbors who judged the fact that they were pregnant.

“If a woman from an Alabama plantation family or a fine family in Mobile got in trouble,” Ross says, “she’d go to Louisa Murray in Mobile, who’d bring her to Ellen Follin in Uptown New Orleans,” and vice versa. So police show up to the house to discover mommies-to-be, but no baby Digby. They start interrogating everyone, all of whom are giving conflicting stories, Ross says, “which raises suspicion and eventually leads to thinking that they should bring in Louisa Murray from Mobile as well.”

They figure she must be Ellen’s accomplice, since she’s tied to the business. So Detective Jourdain picks Murray up, and while the two are on their way back to New Orleans, the baby turns up at the home of famous steamboat captain James Broadwell. “And it’s a complicated story,” says Ross, “but lots of people think Captain Broadwell is part of this plot to abduct Molly Digby.”

He and his wife have longtime relations with Ellen Follin. So the police knock on Ellen’s door, she says there’s no baby, they leave and go to Mobile and, within two days, the captain announces that the baby appeared on his doorstep. Ross agrees one could surmise Molly was passed on to a wealthy, well-respected white man to deliver the baby to the authorities.

But, he’s not arrested. The baby is returned to the Digbys, and Ellen and Louisa go to trial in January of 1871.

“When you think of Southern courtroom race trials, you immediately know how it’s going to turn out,” Ross declares. “If it’s a black defendant, they’re going to lose. And in many ways this might have been the case had it happened a few years earlier or a few decades later.”

But, as Ross states earlier, Reconstruction was a world turned upside down. The prosecutors were chosen by the Republican administration, the defense is held by a Democrat and former Confederate general, and the jury is integrated.

“The ex-Confederate press is gonna win either way,” he says. “If the prosecution fails to make the case, they can say, ‘look how incompetent this black police force is,’ but if the women are convicted they can say, ‘this is the kind of black-on-white crime we can expect in this new era.’”

The jury comes back in just eight minutes and announces the women are not guilty.

“There’s this moment in Reconstruction where white men and black men could serve together on a jury and reach a unanimous verdict of acquitting two African-American women of a sensational crime, because they believe the government did not prove its case.”

Wayne Baquet owns Lil Dizzy’s restaurant in the Treme. “This is the document, signed by all these people, to Abraham Lincoln asking for the right to vote.” He’s pointing to an enlarged historic document that hangs on the wall of his restaurant. “OK, watch who’s on here: Jean-Batiste Jourdain, that’s the detective. My relationship to Detective Jourdain? It’s complicated; I guess you would say he’s my uncle.”

But Wayne didn’t know his uncle was a police detective during the Reconstruction era, until he read Mike’s book. He learned that Jourdain ends up being heavily blamed for failing to nab the conviction of the sisters. He’s demoted from detective to a smaller role in the force, so he leaves and wins a spot in the state legislature. But then Reconstruction ends, and President Rutherford B. Hayes pulls federal troops from the South and leaves the protection of people of color to be enforced on a state-by-state level. This sends Jourdain into a downward spiral, Wayne says.

“He contracts malaria, he loses his position, and following 20 years of this discrimination after having the right to walk around like a free man with his family, something snapped.”

“He’s like this Creole Icarus figure,” Mike comments. “He had flown too close to the sun. And in the 1880s he walks to St. Louis cemetery No. 1 to the Jourdain family grave, sits down on the step, and shoots himself. It’s in some ways a sad metaphor for aspirations and then heartbreak for black Americans and Afro Creoles in New Orleans in the rise and fall of Reconstruction.”

Proof of this? Around 70 years later in the 1930s when the famous Lindbergh kidnapping happens, a reporter—presumably looking to interview a victim of another famous kidnapping—tracks down Molly in New Orleans. The story totally changes, and the reprint says the Afro Creole women were found guilty and convicted of the crime. There’s also no mention of the Afro Creole detective Jourdain; he’s completely written out of the story.

“They could have gone back to copies of the Daily Picayune and found the truth but didn’t,” Mike says. This means the publication of his book is the first time since the 1930s press that the truth has been rediscovered and brought forth.

“Reconstruction is this moment about which many Americans have historical amnesia,” says Mike. “Today we have in our mind’s eye that Reconstruction is going to fail and Jim Crow is going to descend on the South. You could have had a moment where there were reasonable people in the South who were willing to accept perhaps a new order. We know tragically that’s not how it turns out, but it’s not inevitable. And the verdict in the Digby case is one more piece of evidence in that argument.”

TriPod is a production of WWNO New Orleans public radio in collaboration with the Historic New Orleans Collection and the University of New Orleans Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies. Special thanks to Evan Christopher for the opening theme music and to Pizza Delicious on Piety Street for their garlicky additional support! Catch TriPod on the air Thursdays during Morning Edition and again on Mondays during All Things Considered. To hear TriPod anytime, anywhere, subscribe to the podcast on iTunes, and write a review.