The Cemetery Under The French Quarter

October is Louisiana Archeology Month! And this week’s TriPod New Orleans at 300 digs into the discovery, and rediscovery, of New Orleans’ first cemetery.

When you walk around the French Quarter, you see all kinds of tours going by—intimate horse-drawn carriage tours, ghost tours, architectural tours. But most tours don’t touch one of the neighborhood’s most significant landmarks—probably because you can’t see it.

Ryan Gray is an archeologist at the University of New Orleans. He stands on the corner of Burgundy and St. Peter Streets in New Orleans and estimates how many bodies he’s standing on top of. “You know. Six, eight, ten people. There are many people who don’t want to believe that there are quite as many people as I think are buried here.”

But they should believe him. He has proof.

“I was completely by myself,” Gray recalls. “It was really late in the afternoon, and there were birds nesting in the rafters of this building. And it was the most dramatic archeological find that I’ve ever had, the most emotionally compelling one, you know? To all of a sudden be just digging in this clay that has nothing in it, and then, all of a sudden, there’s that piece of wood.”

Gray’s talking about the time he conducted a test dig in the French Quarter in 2011. It was for a property owner preparing to install a pool in the courtyard of his condominiums on Rampart Street. The owner wanted to make sure there was nothing underground that would get in the way of construction.

On Gray’s his last day of digging, he plunged his shovel five feet down, and hit that piece of wood…it was a coffin. “Just below the water table,” Gray adds. “So there’s water kind of filling into the excavation unit at the same time.” And as he’s standing in a five-foot hole with water rising up towards his ankles, Gray thought—jackpot.

“It was almost like a movie—you hit pay dirt,” says Vincent Marcello, the property owner who thought he was close to building a great swimming pool. “But well, we found the mother lode that last possible day.”

By mother lode, he meant the rediscovery of St. Peter Street Cemetery, the city’s first formal burial ground.

Lee Leumas is the director of Archives and Records for the archdiocese in New Orleans. She stands in the archival vault, surrounded by every baptism, marriage, and funeral recorded by the Catholic Church.

Lee Leumas stands in the archival vault of the Archdiocese of New Orleans, reviewing the city’s oldest burial records.

CREDIT LAINE KAPLAN-LEVENSON / WWNO

A lot of people think St Louis Cemetery #1 is the city’s oldest. Those iconic graves are above ground and more accessible to tourists. But those people are wrong.

“Before we had St. Louis #1, we had a cemetery that was the church cemetery, which would have been outside of the city, because the city stops at Dauphine,” says Leumas. “And there was a moat—it’s hard to believe! But there was—that went along Dauphine that encircled the city. And the cemetery then was beyond the moat.”

New Orleans’ footprint was small when it was founded in 1718, about half the size of the current French Quarter. So the Catholic Church created a cemetery outside the city limits, across the moat, to bury the dead. And everyone who died in New Orleans—white people, free people of color, enslaved people—everyone was buried in that single cemetery. Because everyone was Catholic.

“Catholicism was the only religion in the colonial territory,” says Leumas. “If you were French, if you were Spanish, if you were in Louisiana, you had to be Catholic.”

The St. Peter Street Cemetery remained the only burial grounds through the transfer of power from the French to the Spanish in the 1760s. Then, in the 1780s, the Spanish decided the city had outgrown St. Peter Street. It was time for a new cemetery.

“And the Spanish government decides they’re going to expropriate that land,” Leumas says. “And they are then going to start another cemetery, which is St. Louis #1,” the city’s first above-ground cemetery, since they quickly saw the issues presented with below-ground cemeteries, below sea level. “When they do that, though,” she adds, “they don’t dig up the bones and move them.”

The church was appalled by the idea of building on top of bones, on top of sacred land. So they went to the Spanish government and pleaded that they not develop on top of the cemetery.

The city’s response?

“The city did what the city wanted to do,” Leumas laughs. “The government just expropriated the land and built buildings on top of it.”

So the St Peter Street Cemetery was officially closed by 1800, and the Spanish government ignored the Catholic Church’s pleas and developed right on top of the burial grounds. Many of these early 19th Century buildings still stand in the French Quarter today.

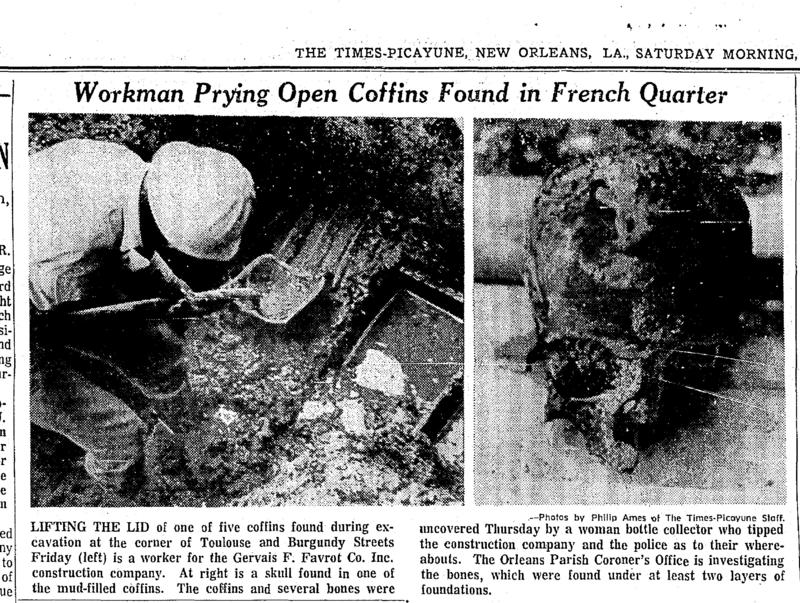

Which brings us back to 2011, when archeologist Ryan Gray’s shovel hit a cypress coffin five feet underground on Vincent Marcello’s property. But Ryan wasn’t the first to discover the cemetery. He says, in 1972, construction in the French Quarter turned up some human bones.

“They were found by an illicit bottle hunter who had snuck onto the site and was digging around and ran across the coffins. And no one really made that big of a deal of it at the time. The coroner’s office said ‘yeah, there are some graves here.’ And then they kept on building.”

A decade later, a developer was doing construction on Rampart and Burgundy streets. He too came across a bunch of remains but told his workers not to say anything so they could finish the project. “I’ve heard that one of the employees got mad at his boss so reported to the newspaper that they were finding and digging through and destroying hundreds of burials,” Gray says. “And people were taking skulls home as souvenirs, and things like that.”

That’s why Gray feels grateful that Vincent Marcello wanted to manage his site responsibly. The original construction plan required a tool called a ditch witch to churn up soil and excavate for the pool. “There would’ve nothing left,” Gray says. “You wouldn’t have even known that there were graves there, if he had brought the ditch witch through.”

Marcello didn’t want to be a ditch witch.

“I wasn’t just going to cover it up and move it along,” says Marcello. “We wanted to do the right thing, and we called the state archeologist and declared it as a site.”

A group of archaeologists from Earth Search lift a (very heavy) 300-year-old cypress coffin out of the test dig site to take to the LSU FACES forensics lab for analysis.

CREDIT RYAN GRAY

Thirteen coffins and two standalone bodies were lifted from the ground and sent to a forensics lab at Louisiana State University. Ginny Listee is a forensic anthropologist and a bio-archaeologist at LSU. She and her team found that the 15 skeletons were of all different ages and genders—infants, toddlers, teenagers, young adults, older people. The studies also determined certain habits among this small cross section of Louisiana’s first inhabitants.

“Two of our males showed evidence of pipe smoking,” Listee says. “So that kind of suggests to us maybe this was a cultural activity, that males in late 1730s of New Orleans liked to smoke their pipes. Another one of our males actually had a dental filling. This is the oldest dental filling in Louisiana.”

Even more incredible, every person discovered was of African or Native American descent. “In the 1778 census, almost half of New Orleans urban population consisted of people of color,” says Listee. “In our group, they were either African or mixed African and Native descent. But there’s nothing that would allow us to say whether they were free people of color or whether they were enslaved.”

Archeologist Ryan Gray says these findings are a nice window into the degree of Native-African mixture in early Louisiana. This gave him an idea. His test dig permit specified that the remains must eventually be reburied in sanctified ground.

“I started thinking about trying to have a public burial event. And since many of the people whose remains were recovered were very likely of Central African descent, it was an appropriate time to bring attention to that aspect.”

The reburial ceremony, leading the 15 bodies to be returned to sanctified ground in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1

CREDIT LEE LEUMAS

St. Augustine Church in the Treme agreed to host a mass for the reburial of this diverse group of early New Orleanians. On April 18, 2015, Choctaw and African dancers and drummers, the Treme Brass Band, and the Black Men of Labor Social Aid and Pleasure Club came together to honor the mixed heritage of black and Native peoples before reburying them in the city’s second Catholic cemetery, St. Louis #1.

“It was an event that ended up drawing on Catholic traditions, west African traditions, and Native American traditions to try and draw all these things together,” says Gray.

This inspired the naming of Vincent Marcello’s pool, once it was completed. “We call it the pool of souls,” Marcello says with a smile. “The tenants actually named it. But were quite content to be on top of a cemetery, you know? We feel like it’s a good space. You know they always say we were a poltergeist site. But the fact is everybody is quite content to know they are swimming in the pool over coffins and stuff. It’s a very peaceful situation. It’s not anything that would be haunted or spooky.”

Peaceful, haunted, or both, hundreds, if not thousands, of bodies—the first people of New Orleans—are still buried beneath this 600 block of Rampart and Burgundy in the French Quarter. And of all the legends that float over and under the city’s oldest streets, this is one to honor, and believe.

TriPod is a production of WWNO—New Orleans Public Radio, in collaboration with the Historic New Orleans Collection and the University of New Orleans Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies.