Solidarity And Revolt Aboard The Slave Ship Creole

This story is part of TriPod: New Orleans at 300. TriPod moves beyond the familiar themes of New Orleans history to focus on forgotten, neglected, or surprising pieces of the city’s past to help us better understand present and future challenges.

A brig is a two-masted ship, a big ship. And brig is the word used for a prison on a ship. And the Brig Creole was an 1800s ship that was meant to deliver 135 enslaved people to New Orleans. Meant being the key word here…

The ship left Virginia on October 30, 1841, with plans to take the same route that dozens of ships took to the port of New Orleans.

Walter Johnson, history professor at Harvard University says, as of 1841, nothing could have been more ordinary than this journey. This was the height of the domestic slave trade in the United States.

“The bulk of the enslaved people who form the labor force in the emerging cotton kingdom are taken from the upper south, as one of the largest forced migrations in human history,” Johnson says.

Ships brought thousands of people into the New Orleans slave market. But those on board the Creole were determined to make moves and not land in the cotton kingdom.

Slave Manifests of Coastwise Vessels Filed at New Orleans, Louisiana, 1807-1860

CREDIT HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION

Britain outlawed the international slave trade with the Slave Trade Act of 1807, and its ships took the lead in policing the high seas, searching ships of other nations. They signed bilateral treaties with Atlantic trading nations such as Portugal, Sweden, France, and others. But there’s one country that responded to this with aw, hell no: America.

“So a British naval crew trying to interdict slave shipments is not allowed to stop a ship that has the American flag,” says Johnson. “What that means, in the words of the historian WEB DuBois, is that through the first half of the 19th century, Old Glory became the slave trader’s flag of choice.”

Other countries became hip to what the U.S. flag meant at sea and started switching flags.

“Say you’re a Spanish slave trader, and you see a British naval ship on the horizon. The first thing the slave traders do is run up the American flag, because that way they are protected by the mantle of American national sovereignty.”

So the United States was notoriously defiant, and we knew it. But back to 1841 and the Brig Creole, sailing the Atlantic under that flag, and everything it represented. A week into the journey, on the night of November 7, William Merritt, one of the slave traders aboard the Creole, went down into the hold.

“He sees Madison Washington, who is one of the slave men,” Johnson says. “He’s out of the hold where he’s supposed to be. There’s a confrontation, and the slave trader escapes from Washington’s grasp and runs back on to the deck of the ship. He hears a shot fired and realizes that some of the slaves in the ship are in revolt, and within four or five hours the slaves have complete control of the ship.”

One slave trader was killed and thrown overboard, and Captain Robert Ensor was wounded. Nineteen slaves were later identified as the rebels responsible for the revolt. They had heard of a ship that had departed from Virginia the year before and shipwrecked in the Bahamas. That was British territory—no slave trade allowed—and those shipwrecked slaves were eventually emancipated by the local British government.

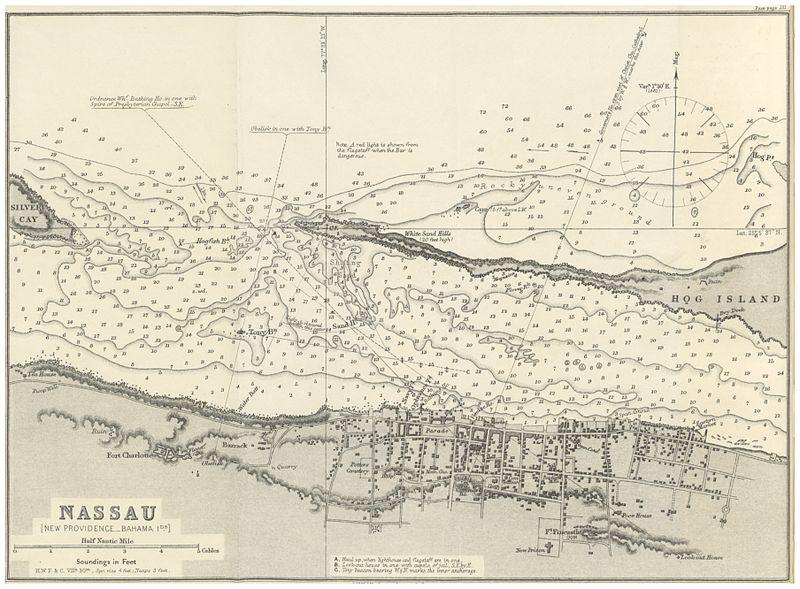

It was with that story in mind that the rebels took command of the Brig Creole and rerouted it to Nassau, Bahamas.

The ship sailed into the port in the Bahamas, and at that point, the 19 rebels kind of stepped down from power to mix in with the rest of the slaves. This was in hopes of not being targeted as criminals, but Johnson says what it also did was allow the white crew to reassert control and let Old Glory do the talking. “Raising the American flag said to the British, ‘you have no interest in this. Just give us back the cargo, and we’ll push on to New Orleans.’”

Not so fast, said the British, who came on board to investigate what happened. They’re told by the Brig Creole crew that a group of slaves rebelled and briefly took control, which is why they’re docked in Nassau. But the Brits responded by saying, “Hey, USA, you can’t claim that a slave revolt has occurred. Not here, anyway.

“Because if there’s no such thing as slavery in the British Empire,” says Johnson, “then there cannot be a slave revolt.”

The white crew just wanted to keep the slaves on board, get back out to sea, and make their profit in New Orleans. But Johnson points out that the community of Nassau at that time was mainly African. It was full of emancipated slaves and the West Indian regiment of Britain’s army. So many of them got into small boats with clubs and went out and positioned themselves around the Creole to protect it from any effort by the white crew to take it away and sail it back to New Orleans.

When the Americans realized they needed to regain control in the harbor, they tried to buy more weapons on shore, but no one in Nassau would sell them weapons. Johnson says there was this revolutionary Black Atlantic, there was the symbol of the American flag moving through the water saying “don’t mess with us, don’t touch us,” there were the British who had abandoned this ideology of slavery. And then all three of those forces came to a head at Nassau. “It’s pretty amazing what they did, right? So there’s a story of the establishment of political solidarity under extreme conditions here.”

Political solidarity surfaced on many levels. As Johnson describes, the community in Nassau surrounded the docked Brig Creole in smaller boats to say “you guys aren’t going anywhere with those slaves—they’re not yours anymore.” The local government defended the community’s actions and gave further support with their army! And the whole town boycotted American business by refusing to sell them weapons. Johnson says that it’s important to remember that before this happened, the original plan was to take over the ship.

“These are 19 people who are from different areas of Virginia, who have not known one another before they met in the slave pen and then on the slave ship in Virginia at the end of October. Within a week, they come to trust one another and to risk their lives on this venture. That’s incredible.”

This is not something the white crew was expecting. Otherwise the ship’s captain, Robert Ensor, would have never brought his family along. In an article Johnson wrote about the incident, he writes:

For what else to call the oblivious confidence with which a man like Ensor brought a fifteen month old child aboard a slave ship. And an aspect of the property he held in his own slaves produced whiteness. A certainty born of history that events would break in his favor. That all would be well.

“And yet he’s willing to lie to himself and say this is going to go all right,” says Johnson. “Just like it always has been before. And it doesn’t. It doesn’t go all right.”

It doesn’t go all right for the slave traders, at least. After months of depositions, insurance claims, and detention in jail, all the slaves, including the 19 rebels, were offered freedom. According to Johnson, ignorance and denial on behalf of the whites on board is what made something like this possible. They chose not to see that this cargo was capable not only of organization, but heroism. He says it all goes back to when the slave trader, William Merritt, first discovered one of his previously obedient slaves out of the hold.

“That moment seems to be an extraordinary moment. This man Merritt, who thought that he was in one kind of history, is forced to confront the idea that something doesn’t make sense. Something’s happening that he doesn’t understand. He says, ‘but you’re the last person I would expect to be out of order on the ship.’ And then it gradually dawns on him, and he starts to run. And that seems to be a moment, a sense of possibility and danger, that is really worth us trying to imagine and capture.”

This boat wide emancipation was celebrated by abolitionists and used in efforts to close the U.S. domestic slave trade. New Orleans was the main engine of that trade and continued to profit from the trade for another 20 years. Although the story of the Brig Creole does not end in New Orleans, it was meant to, and it shows the city’s prominent role within an Atlantic world full of slavery and revolution. Talk about rocking the boat…

TriPod is a production of WWNO New Orleans public radio, in collaboration with the Historic New Orleans collection and the University of New Orleans Midlo center for New Orleans studies. Special thanks to Evan Christopher for the opening theme music. Catch TriPod on the air Thursdays at 8:30 a.m. and Monday afternoons on All Things Considered. You can hear this and every episode of TriPod by subscribing to the podcast on iTunes.