NOLA vs Nature: The Other Biggest Flood In New Orleans History

For the next few episodes, TriPod dives into the city’s messy relationship with water through a new series called NOLA vs Nature. First up: a look at the worst flood in New Orleans history—before Katrina.

A man named Pierre Sauvé is nervously watching this happen. He owns a sugar plantation just above New Orleans, along a particularly sharp bend in the river. This makes him extra vulnerable—and he knows it. Rivers tend first to erode the outer edges of bends.

He does not want his plantation to flood. But then, on May 3, 1849, his levee breaks. And it’s a nightmare.

It was “one of the worst floods in New Orleans history,” says Tulane geography professor Richard Campanella, as he walks up the side of the grassy levee in present-day River Ridge—near the location of the 1849 break.

Today, the levee looks like what you’d expect—a long, man-made hill of dirt that looms above the homes it protects.

“The bike trail is up here. There’s someone walking a dog,” says Campanella, pointing.

But in 1849, what is now a leafy, suburban neighborhood would have been mostly sugarcane fields. And back then, levees were much shorter, usually about four feet high.

“I mean, you can see over it,” says Craig Colten, geography professor at Louisiana State University. “They looked more like bumps in the road, more like big speed bumps made of dirt.”

Colten says in those days, each plantation owner was responsible for building and maintaining his own levees, which means each owner enlisted the enslaved people on their plantation to do the actual building and maintaining.

“This was just people piling up dirt for the most part,” says Colten, “people who didn’t have any engineering training or experience.”

There were no guidelines for how to build a levee, so everyone’s looked a little different—pretty hodgepodge. But one thing they all had in common? They were all low. But the water was high back in the spring of 1849. And on May 3, the levee cracked.

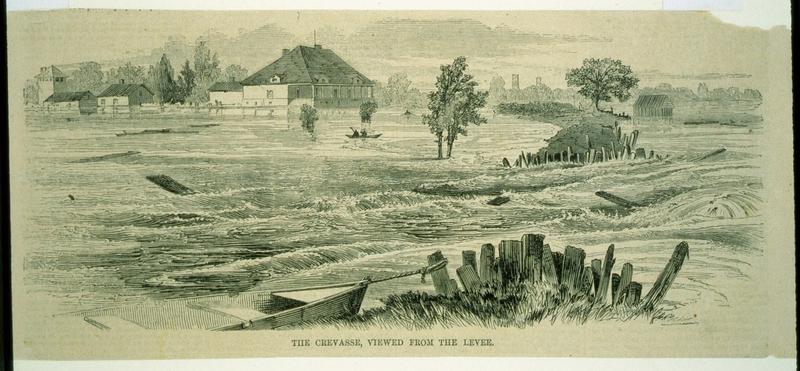

Back then, an open crack in the levee was known as a crevasse, which is French for crevice. Today we’d just call it a levee breach. Richard Campanella says when the levee broke in 1849, the water would have been gushing out of the crevasse.

“And in a matter of hours, there was a breach that was several feet wide,” says Colten.

So Sauvé’s watching the water gush through his dinky levees, and he’s frustrated, but he’s not completely freaking out, yet. He thinks the crevasse can be plugged with sandbags.

“Basically the form it would have taken would have been kind of a bucket brigade,” says Campanella.

People would have been “passing sandbags and gingerly dropping them down and hoping they hold enough for that person to step out on it and extend it,” he says.

So, they try this for a day, and then another day, and then another day.

But this sandbag approach was no match for the crevasse—water kept gushing through. And it started to travel beyond Sauvé’s property.

His plantation was upriver from New Orleans. Back then, most of the area between Sauvé’s plantation and the city of New Orleans was swamp, and it took a few days for those in the city to hear about it. But five days after the initial breach, the water arrived.

“And that’s when it turned from a rural flooding into an urban disaster,” says Richard Campanella.

“We have a great first-person description of it from a Picayune reporter,” says Campanella. “He perched himself up at the highest point in the city at that time—the dome above the St. Charles Hotel. And he says, ‘it looks like Venice.’”

But maybe without the gondolas.

Greg O’Brien, a history professor at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, says people were stranded “right away.”

“Water got as deep as at least six feet in some areas,” says O’Brien. “So pretty dangerous, particularly if people couldn’t swim. The estimates were that more than 200 city squares were under water. About 12,000 people were forced out of their homes. Some of the cemeteries were underwater; gardens were destroyed.”

It had an impact on wildlife, too.

“There were reports of an inordinately high number of alligators and snakes in the city streets,” he says.

Meanwhile, one month after the initial break, the crevasse still hasn’t been plugged. Water is still gushing out, and it’s rising. So, where’s the government this whole time?

“There was no systematic citywide or state response,” says LSU geographer Craig Colten. There was “no relief effort for all these people. People were on their own.”

Quick background here: New Orleans at the time had no centralized government. Instead, there were three separate governments. Each was in charge of a few wards. And because the levee failure happened outside the city, on private property, none of the three governments wanted to take responsibility.

And so, instead of fixing the problem, local officials argued about who should fix the problem, which really means, according to Greg O’Brien, “they do nothing.”

O’Brien says the worst flooding happened in the lowest parts of the city—what today is Treme and the upper French Quarter. The people living there were recent immigrants from Europe and African Americans.

“These were poor people,” says Colten. “They had the least access and the least ability to cope.”

But they had to cope.

“People built makeshift, elevated walkways,” says Colten. “Every boat that was in the city was conscripted and put into use to help people move their furniture out of their flooded houses—to enable people to get from place to place, for people to sell food from these boats.”

Flood maps published after Sauvé’s Crevasse reveal just how widespread the waters were. The total flooded area covered two thirds of today’s city footprint. It was huge.

And as the inundation grew, so did people’s frustrations. The government was MIA, but people started figuring out ways to stick it to the man.

“A grocer named E.B. White very publicly says he will continue to deliver groceries by boat to get to people’s homes,” says historian Greg O’Brien. “But [White] refuses to deliver to any member of the various municipal city councils.”

Absent tangible action from the local government, people take it upon themselves to stop the water. They start building do-it-yourself-style levees in the streets to protect their property. But when they do that, the water moves towards other people’s property—which causes some problems.

People start threatening each other and destroying each other’s personal levees. They form posses and pull out weapons. There’s no record of anyone being killed as a result of these tiffs, but tensions ran high.

Meanwhile, some people wanted to see the crevasse for themselves, which would have been quite a sight.

An advertisement for the steamboat tour of the crevasse site in the Times Picayune, May 13th 1849 CREDIT NOLA.COM

A month after the initial breach, the crack had widened to 300 feet—the length of a football field!

“It was a visual spectacle,” says Craig Colten. “The steamboat companies would run daily packets, and they would have bands on board so people could listen to music while they’re chugging up the river. They pass back and forth in front of the breach so people could see the water, churning through this break in the levee.”

The city did eventually get its act together. Once it became clear Sauvé couldn’t handle the breach on his own, officials from the three New Orleans governments formed a committee to try to solve the problem. They sent some engineers to try to plug it, but those engineers struggled at first. They tried dumping tons of sandbags—that didn’t work. They tried sinking a riverboat, hoping it would get stuck in the hole and clog it up—that didn’t work either.

Map of city showing four proposed plans to protect the city from future river floods

CREDIT NEW ORLEANS DAILY DELTA, JULY 1, 1849 / HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION

Finally, on June 20—a full 48 days after the crevasse opened—the river goes down. Engineers build a floodgate, and the big flood of 1849 is finally over.

Tulane geographer Richard Campanella says people would have been talking about that year for many more years to come. He calls it “the Katrina of the 1800s. A watershed moment.”

Sauvé’s Crevasse put a lot of pressure on the city and state to make some big changes. For one, it became something of a rallying cry for better levees along the Mississippi River. There was actually legislation in the works, prior to the breach of Sauvé’s levee, that sought to transfer levee management responsibilities from private landowners to the state of Louisiana. But the crevasse likely sped that process along, and in a few years the state took over levee management.

It wasn’t just the levees, either. People realized city government needed an overhaul too.

“Having three municipalities really didn’t work,” says Colten. “They needed to re-consolidate and have one mayor, one city council, and one city government.”

So they do. And some people feel comforted that now, one government can tackle these big problems. People at the back of town, on the low ground, remain skeptical. But at least for those people on the high ground, near the newly engineered levees—they’re more optimistic. They’re thinking the next time something like this happens, it won’t be nearly as bad.

The city is divided between those who have less faith, and those who think maybe, just maybe, that was the last big flood.

TriPod is a production of WWNO New Orleans Public Radio in collaboration with the Historic New Orleans Collection and the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at UNO. Special thanks to Evan Christopher for the opening theme music, our editor Eve Abrams, the TriPod editorial committee, and interns Tori Bush and Michael Ceraso. Subscribe to the show on your favorite podcast app, and rate the show on iTunes! You’ll be SO glad you did, and we’ll be forever grateful.