NOLA vs Nature: The Blessing And Curse Of The Wood Screw Pump

TriPod: New Orleans at 300 returns with its NOLA versus Nature series. This week: WWNO’s Laine Kaplan-Levenson and Travis Lux look at the city’s drainage pumps and the man behind their design—Albert Baldwin Wood.

New Orleans is below sea level. You know this, and certainly, if you were here this past August, you really know this. Almost a foot of rain fell over a couple hours, and parts of town were knee deep in water.

The Sewerage and Water Board caught a lot of flack for this: people lost a lot of faith when they found out that the city’s pumps and generators—things that were supposed to keep the city from flooding—were broken.

Joe Becker worked for the Sewerage and Water Board for 30 years and was actually the superintendent. Becker retired last summer after the flood drama. You might have some feelings about him or the Sewerage and Water Board. But Becker really knows his pumps. Albert Baldwin Wood. That’s our guy.

Pumping Station #1, also known as the Baldwin Wood Pumping Station

CREDIT LAINE KAPLAN-LEVENSON / WWNOHe recently took me on a tour of Pumping Station #1—right in the neutral ground of Broad street before it hitsWashington Avenue. These are the pumps that keep the city from flooding during a big rain. They’ve been doing their job for more than 100 years. “This is the wood screw pump,” Becker says. “There’s no wood in it, it’s not made out of wood at all. This is named after the person who invented the design—A. Baldwin Wood.”

“He basically was a loner,” said Ralph Wood Pringle in his living room in Mississippi. Pringle is Baldwin Wood’s great-nephew. “He liked being by himself. He dressed in khaki pants most of the time with a khaki shirt. I never saw him wear anything other than that. He was not the average person.”

Baldwin Wood grew up in New Orleans and stayed for college—Tulane Engineering. He couldn’t help but invent stuff; there’s this story I read while researching Wood about how he and a fellow classmate built a wireless walkie talkie type thing so that they could communicate between classrooms. This was around 1899.

Let’s think about the year 1899 for a second. We’re in the Progressive Era. William McKinley is president. Scott Joplin’s Maple Leaf Rag was published. And there’s widespread reform across the country. Everywhere, people are pushing their elected officials for new infrastructure to make their cities better…parks, playgrounds, schools, trees. And in New Orleans—draining the swamp.

Richard Campanella is a geographer at Tulane. “People literally feared and hated the backswamp,” he told me, the backswamp being what we now call Lakeview, Gentilly, and all of City Park. But in the 1890s, that was 100% swamp, which meant that New Orleans’ backyard was filled with mosquitoes and, with them, deadly waterborne illnesses: malaria, yellow fever, dengue. So everyone thought draining the swamp was a good idea.

People had wanted to do this for years—wanted, tried, and failed. Now enter Baldwin Wood. He graduates from Tulane and goes to work for the brand spanking new Sewerage and Water Board. He takes a look around at the existing drainage system and notices that the pumps are helping with some of the flooding issues. But they’re no match for the backswamp. He’s sure he can invent something better, faster, stronger. And a little over a decade later, he does.

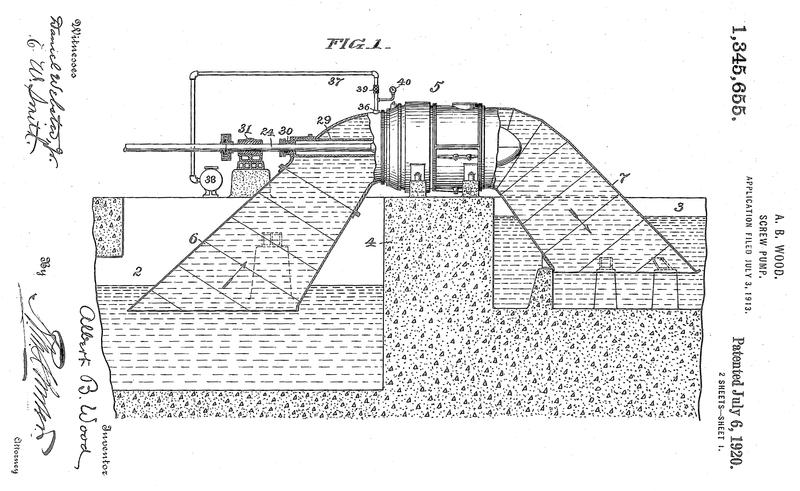

Diagram of Patent 1,345,655 Wood Screw Pump from US Patent Office. Filed 1913; Patent finalized 1920

CREDIT US PATENT OFFICE

“Imagine a jet engine for water,” says Campanella, in regard to how Baldwin Wood’s pump works. It’s like a giant straw, using suction to pull water from a lower elevation to a higher elevation. Right, Campanella says, “except that instead of your breath doing the lifting, it’s this fast speed impeller.” The impeller looks like a huge fan. When it rotates, it sucks up water from one place to another. In this case, from the lower ground to higher ground, so that the water can flow down into the lake. That’s it. That’s how the wood screw pump works. And Wood’s pump could take on way more water per second than the other pumps.

Campanella writes that this municipal drainage system that was powered by the wood screw pump is “the single most dramatic transformation of the New Orleans cityscape.” And Campanella says his statement is easily defended. “All you have to do,” Campanella says, “is take a look at the urban footprint in 1890, and take a look at the footprint by the time the municipal drainage system had its full effect, which was only a few decades later. The city that you will see prior is essentially a crescent-shaped city.” It’s crescent-shaped, because it’s hugging the river. After Baldwin Wood’s pump hits the scene, the city spreads all the way from the river to the lake. And all of this was possible because his pump was good enough to drain the backswamp—to turn all that soggy muck into dry land.

And people are thrilled. All those mosquitoes? Gone. All those diseases? Gone. Plus, the city’s bigger. Developers love it; new neighborhoods pop up. All of this makes Wood, the inventor of this breakthrough wood screw pump design, famous. We’ll get back to that later.

There were downsides. The wood screw pump was a blessing and a curse for the city of New Orleans. As most of us know now, when you pump the water out, the soil shrivels up, and the land sinks. And the more we pump, the farther we sink—subsidence. “This is not a normal condition. It is not a natural condition, says Richard Campanella, of subsidence. “So it’s a package deal. If you love the neighborhoods that came out of this,” then you also have to recognize that these neighborhoods became bowls that could easily be filled with water.

Craig Colten is a geographer at LSU. “I don’t think the engineers were thinking about the unintended consequences of these things.” He says subsidence is an unintended environmental consequence of Wood’s pumps. But there were social impacts, too. As new neighborhoods opened up along the lakefront in the early 20th century, developers, with the sanction of city officials, kept African Americans from buying into them.

“Basically it created much more racial segregation,” says Colten. “Areas that were low areas, that had been working class white neighborhoods, became primarily black neighborhoods,” such as parts of Central City. And then all the new lakefront real estate became a very white neighborhood. And so the racial geography of the city changed as the system went into place.

Colten says there were city agreements that prohibited black people from living in those new areas on the lakefront. “If you bought a piece of property there, the deed said you couldn’t allow a black person to live in that house.”

This pattern of residential segregation, once established, would accelerate over the 20th century and is still evident today. That’s why Colten is uncomfortable completely glorifying Wood’s pumps. “We need to recognize that they were innovations, and that’s entirely appropriate. But I think we need to look at them in their totality, the total range of contributions and influences.”

Back to today. Well, almost today. There were two big floods in New Orleans this summer. One day in August, we had more than nine inches in a little less than three hours. That’s more than the drainage system, a system built more than 100 years ago, can handle. The drainage system that we have, while it’s massive, can only handle about a half an inch of rain in an hour. Maybe less.

The wood screw pump is still in action at the Pumping Station #1.

CREDIT LAINE KAPLAN-LEVENSON / WWNO

“If all the pumps were working,” defends former SWB superintendant Joe Becker, “if all the pumps weregenerating power at 100% effectiveness, as much as we could, we were going to have a flood from that. Because the pumps just can’t keep up with that.”

Climate change is already making those storms more intense and more common. And so even if the pumps still do what they were built to, is that enough? Craig Colten says no. “The fact that we’re still relying on them so heavily is really a sign of serious neglect. Those machines are taken care of with exquisite care. But to continue relying on early 20th century technology in the 21st century, when the landscape of the city has changed so much?

“Doesn’t cut it anymore,” he adds. “How do we find ways to build adequate technology that will last us into the next century?”

After Wood invented his wood screw pump circa 1915, he became kind of famous. Cities around the world were asking him to visit them—especially the Netherlands. Dutch officials tried to organize a meeting with Wood at the request of the Queen of Holland. But get this…Wood refused to leave Louisiana. A Dutch engineer spokesman pleaded with Wood and wrote, “her majesty’s government wants you to supply pumps for Holland.” Wood wrote back, “yes, I understand. I’ll be back Tuesday…but now, I’m going fishing.”

Ralph Wood Pringle in his home holding a picture of his great-uncle Baldwin Wood on board his sloop, the Nydia

CREDIT LAINE KAPLAN-LEVENSON / WWNO

Baldwin Wood’s grand-nephew says this makes sense, because Wood’s two favorite things were being out on the water and New Orleans. “The city was home to him. He took pride that his pumps actually allowed the city to be developed.” And he lived long enough to see the city change so drastically because of his invention.

When asked what he thinks Wood would have to say about the current situation the city of New Orleans and the Sewerage and Water Board are in, Pringle replied of his great uncle, “he would have probably reinvented another pump himself.”

TriPod is a production of WWNO, in collaboration with the Historic New Orleans Collection and the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at UNO. Special thanks to the New Orleans-based weather and climate project, I See Change, for co-reporting some of this episode. They’re creating a community record of recent storm events. You can share YOUR flooding stories and photos with them on ISeeChange.org. This story on Baldwin Wood is part of our NOLA vs Nature series.

Support for the Coastal Desk comes from the Walton Family Foundation, the Greater New Orleans Foundation, and local listeners.