More Than A Runaway: Maroons In Louisiana

You live in a cave, six feet underground. You’re surrounded by wild animals, swarms of mosquitos, thick mud, and you can only come out at night. Why? Because it beats being a slave.

“They could live there for five, seven, ten years,” says Sylviane Diouf, director of the Lapidus Center for the Historical Analysis of Transatlantic Slavery at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, New York.

“And that really is one indictment against enslavement, when you’re ready to live in those conditions, and have your children live in those conditions, rather than be slaves,” she says.

Diouf is talking about Maroons, who were runaway slaves…kind of.

“So most runaways actually run away to the cities and try to pass there as free. The Maroons, on the other hand, were looking illegally for freedom, but on their own terms. So they were looking for their way to establish their communities in areas that nobody had control over.”

If you’ve heard of Maroons, you’ve probably heard of Caribbean or South American groups. That’s because there was no book on Maroons in America, until Diouf wrote one in 2014. There were thousands of Maroons at any given point up from the earliest slave arrivals until the end of the Civil War. Many were in Louisiana, in areas that were not too far away from the city centers but were difficult to access.

“The militia and others sometimes had reluctance to go into those swampy areas and forests,” says Diouf. “You had to wade into the water to your neck, with the mosquitoes and all the wild animals. And the Maroons played on that very well.”

Just in case search parties did come knocking, and they did come knocking, many Maroons in higher and drier areas literally lived underground. Diouf is fascinated by these caves.

Living in a Hollow Tree, in William Still’s The Underground Railroad, 1872

CREDIT NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY, SCHOMBURG CENTER FOR RESEARCH IN BLACK CULTURE

“When you look at those caves, some were really little houses, with stoves, with furniture, beds, and all those kinds of things,” she says. “You also had women who gave birth in those caves, sometimes by themselves.”

To Maroons, this was not only preferable to being a slave, but preferable to trying to get by in the existing society. There were fugitive slaves trying to make it in the urban centers. But even that seemed less desirable than digging a hole in the ground and raising your child. “It’s absolutely unimaginable,” Diouf says.

And yet, they kept their old lives at arms’ length. When Maroons escaped the city or plantation, they didn’t go too far. They went to the woods, but really the edge of the woods, known as the borderlands.

Sometimes groups of Maroons—which were small camps of fewer than 20 people—established settlements that were technically still on their old owner’s property. It was just uncultivated land the whites were unfamiliar with! This was to have access to the resources in the big city or the big house.

“In New Orleans, on the outskirts, you had Maroons living there. And then at night they would go to the city and take whatever they needed—food and other things,” Diouf says. “It’s so extraordinary that people were able to live outside of slave society while at the same time taking advantage of it in many ways.”

And it was designed as such. Often, one member of the family would remain on the plantation to be able to help the others.

This reproduction of a 1798 Spanish map of the plantations around New Orleans shows the numerous cypress swamps, many of which were inhabited by Maroons.

CREDIT THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION / LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

“Families would have to weigh, ‘what is the advantage?’” Diouf explains. “‘Is it better for all of us to be in the cave or to be in a community somewhere, or is it better for one or two of us to stay on the plantation to be able to help give us news, intelligence about what’s going on, about when the militia is coming with the dogs?’”

“I remember a man who was living very far from his wife, and he came to see her three times a week,” Diouf says. “So the owner was actually like ‘you know, he must be around, because both your two children look exactly like the other two.’ And she always said ‘oh no, it’s been years since I’ve seen him, since he was sold away,’ and this and that and the other. But they kept having children.”

So marronage—the strategy of resistance by which slaves would run away and return—could keep families together, which is what this type of resistance was about: taking back what was theirs.

“Stealing was if somebody stole from another person when enslaved,” Diouf says. “That’s why stealing from white people was not stealing. So whatever they were taking they were entitled to it, because they had actually produced it.”

Raiding the plantations was one way of survival. Another was doing work for hire—actually getting paid. Already being in the woods, Maroons in Louisiana tapped into the lumber industry. A lot of times, they would work for white people to cut timber and turn it into logs. Diouf says the whites didn’t report them, because they paid Maroons less than they would pay anyone else.

“It was a cheap labor force because they could not really complain,” she says. “But it was useful for them, because they got what they needed.”

Sometimes, other slaves would outsource their own chores, and have Maroons do their work for them, and strike some sort of trade. So they were outsiders, but not cut off. That’s what made them so threatening.

“Slave owners were afraid that the presence of Maroons would corrupt the people, because they said that they noted insolence among the slaves,” Diouf says. “It was like, ‘well if you’re doing all this to me, then you know I can go and join the Maroons.’”

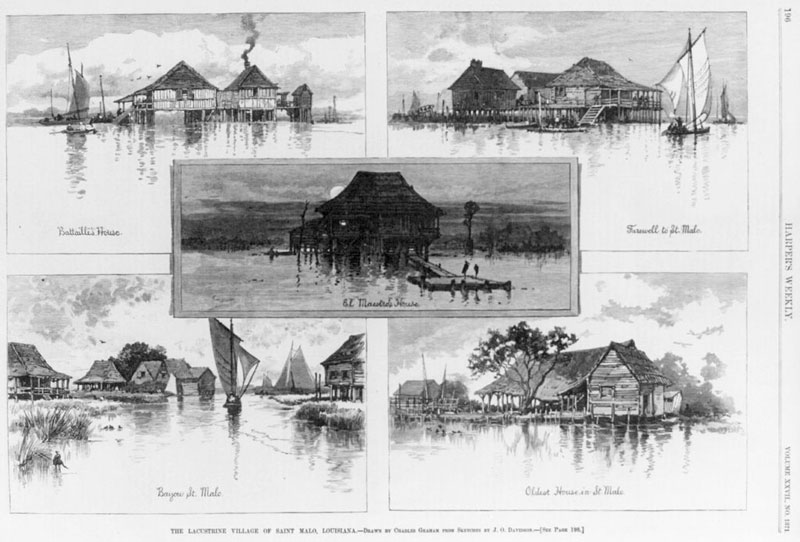

That’s what made the government crack down on the largest nomadic Maroon settlement in Louisiana, St. Malo, lead by Jean Malo, one of the only identifiable Maroon leaders in the United States.

While most Maroon groups didn’t break into double digits, St. Malo had a population of more than 50, until it was ultimately defeated by the Spanish under Governor Esteban Miro. They captured Malo and fellow organizers and hanged them, making an example of the rebels against the slave system.

“It’s the psyche of they were ready to do anything to be free, according to their own rules, without having to live in a northern society where they were second, third, fourth class citizens, even if they were nominally free,” Diouf says.

“It’s not the kind of pseudo freedom of living in a city in the South where you pass as a free man or a free woman, but you are not. This is real freedom. And to a planter who could not understand why a Maroon did not return when, if he had been sick, he had frostbite, it was a very difficult time. And the man told him, ‘I taste how it is to be free, and I didn’t come back.’”

TriPod is a production of WWNO—New Orleans Public Radio, in collaboration with the Historic New Orleans Collection and the University of New Orleans Midlo Center for New Orleans studies. Special thanks to Evan Christopher for the opening theme music.

Catch TriPod on the air Thursdays at 8:30 a.m. and Monday afternoons on All Things Considered, and subscribe to the podcast on iTunes to get all the latest episodes delivered to you on the go.