How The Germans Brought Gymnastics To New Orleans

When you think about gymnastics—parallel bars, the pommel horse, ropes—what else pops into your head? Fighting Napoleon and frosted beer mugs? Me too!

Here’s how the Germans brought gymnastics to New Orleans.

She’s talking about Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, a.k.a. the “father of gymnastics,” a.k.a. “the turnvater.” Jahn lived from 1778-1852, “and that was a very exciting period in German history,” says Malm. “For one thing, it included the Napoleonic wars.”

Their slogan was sound body, sound mind, and they placed equal emphasis on liberal intellect and physical activity. Hence gymnastics and gym clubs, called turnvereins.

The turnvereins were filled with bars and swings and mats and countless equipment to climb on, jump from, and lift. Their version of free weights were called Indian clubs, which look more like modern day bowling pins than dumbbells. Turnvereins were all over Germany—think Planet Fitness, but old school, and with a social consciousness.

So the turnvereins are going, people are pumping Indian clubs, getting buff. Then, in 1848, there was a revolution in Germany. The revolutionaries, known as the ‘48ers, wanted a unified Germany, a democracy, and human rights.

But their revolution failed, says Malm. “And a lot of the people, the leaders in this group, had to leave Germany. And most of them came to the United States.” Jahn, the turnvater, went to jail, along with a lot of other Turner leaders. His followers fled, and many of these arriving expats helped bring the Turner movement to the United States.

The first two turnvereins opened in Cincinnati and New York in 1848 and a third in New Orleans in 1851. Before long there were a few more, including one on Lafayette and O’Keefe streets in the Central Business District, in a building named Turners Hall. The building now houses the offices of the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities.

Turners Hall, 938 Lafayette Street, New Orleans. Designed by William Thiel and completed in 1868 for the German Turners Society. Converted to offices in 1980.

CREDIT READING TOM / FLICKR

Most of these ’48ers settled in the north and Midwest. The few that did come down South felt like misfits—their views didn’t align with the antebellum times. The turnverein was their community. Then there were the German immigrants who were already here and excited to join the turnvereins for purely social reasons, to have a place to meet other Germans, speak German, and just be German.

“They had a bar inside, of course,” says Louis Mayer, whose grandfather, Gustav Frederick Mayer, was one of the earlier members of the turnverein. “If you have Germans, you’re gonna have beer. You’re definitely gonna have that.”

Not only was Gustav Mayer a turnverein member, he lived in one. He and his family lived in an apartment in the back of a club on Clio Street from 1915-1923.

A group picture at the turnverein on Clio Street. Louis Mayer’s grandfather is in the center of the image with Mr. Heine, another member of the Turnverein. Both are holding beer steins. His grandmother is to the left, with his Uncle Gus as a very young child.

CREDIT LOUIS MAYER

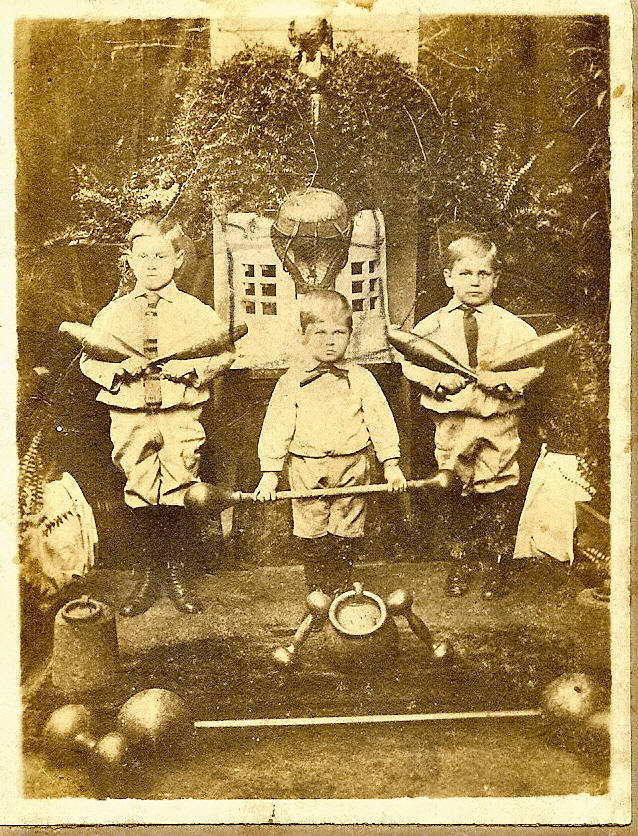

Mayer was actually a gym teacher and gave lessons to other members at the turnverein. He trained people in tumbling, free weights, fencing, and forming the human pyramid.

Dorothea Dell’s father, Adolph Julius Fischer, was the top of the pyramid at the Clio Street Turnverein in the 1920s. “That actually is a rather dangerous position,” Dell adds. “And I do believe that he stated that he was the lightest and the most supple, and probably the most carefree!”

The Historic New Orleans Collection owns and houses this record book of the turnverein pyramid section, from 1900-1914.

CREDIT LAINE KAPLAN-LEVENSON / WWNO

She also grew up hearing how important it was to stay in shape. “He emphasized that we eat properly, and we did. We were active. As a girl I did jump rope and hopscotch, and it was fun! That’s what you did.”

Gymnastics was clearly the bread and butter of the turnverein, but these clubs were more than athletic facilities—they rented their spaces out for marriage ceremonies, masquerade balls, Oktoberfests. And along with the athletic section, turnverein had singing groups, swimming and fencing clubs, and Sunday afternoon beer drinking.

It was important for Germans to have a place for these activities, especially during the time period that Louis’s family lived on Clio Street.

“Remember the dates were 1915-1923,” Mayer reiterates. “World War I started in 1914, and the United States came in 1917, 1918. The public didn’t like Germans very much. Daddy went to public schools down the block where he lived. And he constantly had fights, and they knew where he lived. He lived in the turnverein, and that was German.”

So America went to war with Germany, and German-Americans suddenly felt treated with suspicion by their neighbors. This created an even stronger craving for a German haven. Louis’s father told stories of being bullied at school, so he took advantage of the turnverein, too.

“He would come back and have lunch at home. And Daddy told me that Grandpa would insist that they drink their beer, even as young kids. And if they didn’t drink the beer, he would get upset; he would think something was wrong with them. And they could drink as much as two bottles of beer for lunch! And he would go back to school and would tell me he’d be tipsy going back to school!”

Anti-German sentiment lingered after the war, and German-Americans continued to become more American. In 1928, the remaining German clubs of New Orleans consolidated as the Deutsches Haus and moved into a building in the 200 block of South Galvez Street.

No one knows for sure how long followers of the Turner Movement continued gymnastics at Deutsches Haus, but the sport eventually lost its German identity. Daniel Hammer, Deputy Director of the Historic New Orleans Collection, says this may go back to the ongoing process of cultural assimilation following the war. Other activities took hold, such as bowling.

“Bowling was a famous pastime at Deutsches Haus,” Hammer says. “And maybe in their minds somewhere that athletic activity was an extension of the turnen they used to do. A metamorphosis of old ideas into new ideas.”

Daniel Hammer in the Historic New Orleans Collection, paging through a book of Turnverein records from the 1920s.

CREDIT LAINE KAPLAN-LEVENSON / WWNO

In some ways, though, we’ve all experienced a little turnverein. If you went to public school, you probably did some type of Presidential Fitness Test—running a mile, doing ten pull-ups, 100 crunches, that sort of thing, for a little certificate at the end. Brigitta Malm says you can thank the Turners for that.

“In fact, when they first started in the 1820s, they actually trained the teachers to give athletic instruction,” she says. “That’s how it got into the public schools.”

So even though such a small group of people actually participated in the turnvereins, the entire youth of the city of New Orleans was, sort of, in a turnverein, by going to school and taking gym.

TriPod is a production of WWNO New Orleans Public Radio, in collaboration with the Historic New Orleans Collection and the University of New Orleans Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies.

Catch TriPod on the air Thursdays at 8:30 a.m. and Monday afternoons on All Things Considered, and subscribe to the podcast on iTunes to get all the latest episodes delivered to you on the go.