Home Away From Home: A Haitian In Exile Finds New Orleans

This story is part of TriPod: New Orleans at 300. Tripod moves beyond the familiar themes of New Orleans history to focus on forgotten, neglected, or surprising pieces of the city’s past to help us better understand present and future challenges.

Maryse Dejean was sitting at the Mardi Gras Hall of Fame dinner a few weeks ago when she met Renette Hall, the editor of the Louisiana Weekly. They were at the same table.

“She really reminded me of relatives and people in Haiti,” Dejean recalls. “She was wearing this beautiful crocheted dress. And at one time in Haiti, you know, that was all the rage—crocheted dresses that just kind of fell perfectly on anybody’s figure. And she looked Haitian to me. And in fact I found that in many faces in New Orleans.”

The connection between Haiti and New Orleans traces back to 1698 when Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville, (whose brother Bienville founded New Orleans), left the French owned colony of Saint-Domingue—present day Haiti—for Biloxi. There he established one of the first colonies in the gulf south.

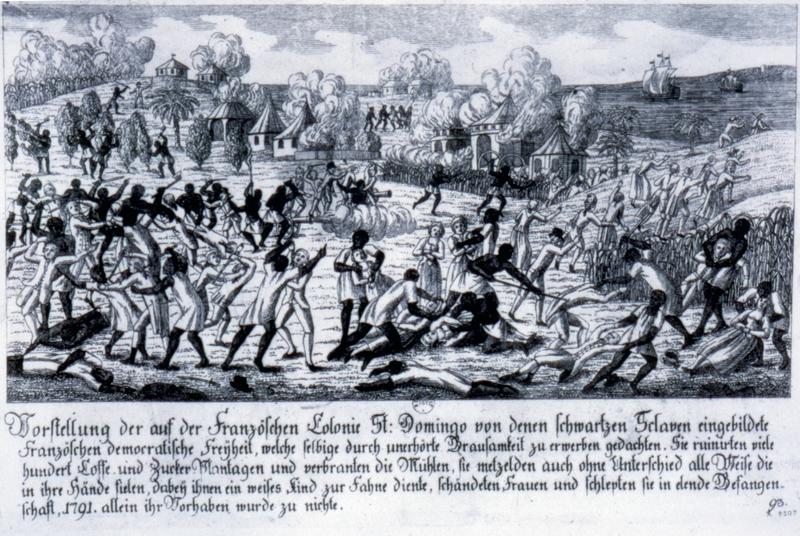

Jump ahead a century to the Haitian Revolution. From 1791 to 1804, people fled to American port cities like New York, Baltimore, Philadelphia and New Orleans.

Saint-Domingue was renamed Haiti. This was the first wave of Haitian immigration. In 1809, a second wave came from Cuba, where white planters and free people of color had taken refuge with people they claimed as their slaves, even though by French law they had already been freed.

Spain had declared war against France, so all the French Saint-Domingue refugees got out of Spain-owned Cuba. Nine thousand people went to Louisiana (it was close, people spoke French)—equal thirds white, free people of color, and slaves. This doubled the size of New Orleans.

Carte De L’Isle De St. Domingue une des Grandes Antilles.

CREDIT THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION. (1993.2.21)

That’s the power-hour version. N’inquiete pas—we’ll return to this stuff in greater detail later in TriPod. But back to Maryse Dejean’s story, which starts in the 1950s with the 40th president of Haiti, Francois Duvalier, also known as Papa Doc.

Maryse Dejean holds a photograph of her uncle (who later became her father) on a visit to Washington, D.C. to meet with President Truman and fellow ambassadors to the United States. This is the first digital publishing of this image.

CREDIT LAINE KAPLAN-LEVENSON / WWNO

The Duvalier regime came to power in 1957, which changed Dejean’s life forever. Her father was executed in the early 1960s by the government, for reasons she still doesn’t know. Dejean was adopted by her aunt and uncle, who she then called Mother and Father. But when her uncle tried to retire, it became clear they weren’t safe either.

A close-up of the photograph depicting Maryse Dejean’s father posing with President Truman and fellow ambassadors to the United States. This was before Papa Doc took over Haiti.

CREDIT LAINE KAPLAN-LEVENSON / WWNO

She later asked her father why he chose to retire when Papa Doc came into power. “He said, ‘intuitively, I didn’t get a good feeling. And I sensed there was something that was evil about it, so I politely excused myself. I said that I wanted to go back to the countryside to teach. And that I was retiring from the diplomatic life.’”

That same day in the afternoon, people came to the Dejean house to warn her mother not to let her husband come home. “They said, ‘he has to leave right away, right away. Because his name is on a list.’ And so my father did not come back to the house, and he went into hiding for close to six months.”

This happened to anyone who politely excused themselves from participating in the Duvalier government. So the Dejean family left and made their way through Mexico to Washington, D.C. She was four years old. After more bouncing around, Dejean attended high school, college and graduate school in D.C., too.

The family longed to return to Haiti, but when president Papa Doc died in 1971, his son Jean-Claude, Baby Doc took over. This meant the Dejean family could still not return. Meanwhile, shortly after Dejean got her master’s degree, she came to New Orleans on a whim, and surprisingly felt at home.

“I didn’t really know what to expect in coming to New Orleans, but the architecture really just triggered something in my memory, and I felt that I could be in Haiti. And at the time, all of us were still in exile, you know. We couldn’t go back. It wasn’t until about 1986, I believe, that my mother and father actually went back to Haiti. I believe that was the ousting of Baby Doc. That was close to a little over 30 years, you know, since I had been there. So over the years realize that this is a next best place to be, if I can’t return to Haiti.”

Dejean’s father was not thrilled about this move. He didn’t understand why his daughter would choose to live in the American South, a place so scarred by segregation. It took him years to visit. But when he did, he was amazed, Dejean remembers.

“We went to the Treme, and he saw the architecture, he sampled the food, he talked to people. I could tell he was really enchanted. Because in him, I saw the same connection that I felt when I first arrived in New Orleans.”

Dejean refers to herself as a hybrid. She’s barely lived in Haiti and has spent most of her life in New Orleans. She just tries to marry the two.

“Haitians in general do very well, because we have a sense of self, and that was a gift of the ancestors, you know, who fought for freedom. And when you have that, then you can kind of move through different countries. And you can recognize opportunities and no matter what, you’re going to do the very best. You’ve got to carry on with that in both paying respects to what they did for you and also just acknowledging the strength that it inherently gave you.”

Dejean’s history never leaves her. She says anyone affected by Papa Doc and the Duvalier regime still suffers.

“The story that I’m telling you, this is really the first time that I can articulate it. Because I have never been able to say that… you know, I have an adopted family. And I have a biological family. And this is what happened, the trauma of it all. Because there was always a feeling that one must keep secrets, a secret so that you would protect, you know, the other side of the family.”

Dejean says that, in some ways, by telling this story, she is finally out of hiding.

TriPod is a production of WWNO—New Orleans Public Radio, in collaboration with the Historic New Orleans Collection and the University of New Orleans Midlo Center for New Orleans studies. Special thanks to Evan Christopher for the theme music.

Catch Tripod on the air Thursdays at 8:30 a.m. and Monday afternoons on All Things Considered.