Founding New Orleans, The Vagabond City

Today we launch our new Tricentennial series, TriPod: New Orleans at 300. Tri (for the city’s three centuries), Pod (for podcast), and Tripod, the tool used to steady the image when you’re trying to capture something.

TriPod moves beyond the familiar themes of New Orleans history to focus on forgotten, neglected, or surprising pieces of the city’s past and gives us a better understanding of present and future challenges.

This series will pull up some of New Orleans’ lost and neglected past, things that put what we think we know into question, as this city comes up on its tricentennial in 2018.

There are three centuries to cover, so why not start at the beginning—or, at least, one guy’s beginning—the European beginning. The Euro-ginning.

It’s August 1717. The Company of the West manages all business in the French colonies in North America, and it’s just received its Louisiana Charter. For years, French explorers have traversed the Gulf region of North America, but it’s not until this Louisiana Charter that the French Crown decides to build a town named after France’s Duke of Orléans, who was ruling France for baby Louis XV. This town is called New Orleans.

To be clear, the history of this place does not start with European capitalists. It started at least 600 years before all this with indigenous communities who lived where the French Quarter now sits.

Back to 1717. Enter Canadian Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville. He and his brother Iberville were quite the dynamic duo, exploring the Gulf coast. And like all colonialists in the Americas, they depended on the expertise of existing locals, like the Bayogoula people.

Sometime between March and May the next year, Bienville cut the first canebrake—a bamboo-like native plant—and New Orleans became official. There was only one thing the city’s founder needed. Well, actually, there were a lot of things he needed, but first and foremost, he needed people. One small problem: no one wanted to come.

“New Orleans and Louisiana were bywords in France, they sent a shiver of fear up somebody’s spine,” says Lawrence Powell, author of The Accidental City: Improvising New Orleans. Powell describes these early colonial years as a tenuous struggle, not only in terms of development, but for mere survival. The sheer force of the natural elements—the climate, the terrain, and the unforgiving vegetation—made it nearly impossible to create a sense of civilization, not to mention to live past age 40.

When Bienville founded the city, fellow French explorer Jean-Baptiste Bénard de la Harpe wrote:

“In the month of March, 1718, the New Orleans establishment was begun in flat and swampy ground fit only for growing rice; the air is fever-laden, and an infinity of mosquitoes cause further inconvenience in summer.”

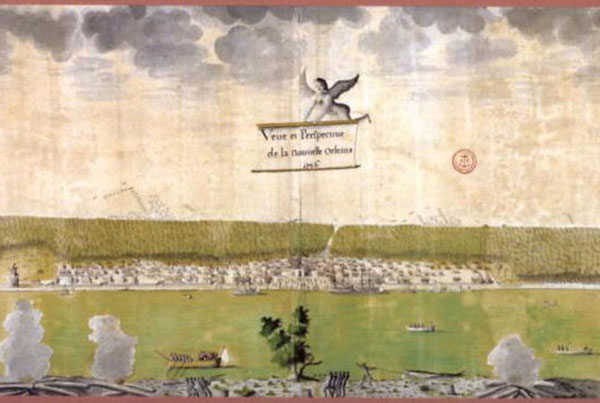

Plan de la Nouvelle Orleans Capitale de la Louisiana, 1728

Despite these conditions, the ever-stubborn Bienville was determined to set roots in what geographer Richard Campanella describes as a strategic situation, more so than a site. In his book Bienville’s Dilemma, Campanella says, “New Orleans was just as poorly located as a city, or more precisely as a dwelling place, as it is excellently located as a commercial site.” Basically, it was the perfect place to set up shop, and the worst place to set up camp.

Fast forward to June 10, 1718, when Bienville sends this update to The Company of the West money men back in Paris:

“We are working on New Orleans with such diligence as the dearth of workmen will allow. I remained for ten days, to hurry on the work, and was grieved to see so few people engaged on a task which required at least a hundred times the number.”

Somewhere around 50 convicts had been sent over from Canada and the other existing colonies, such as Biloxi, to help Bienville clear the site and build huts. But they refused to work, or they fled, or they straight up died. Bienville needed to prove to France that he could successfully build a city. To do that, he not only needed manpower, he needed a population.

Let’s jump over to Europe; in this early part of the 18th century, the War of Spanish Succession had just ended, and tons of ex-soldiers were returning home to France, unemployed and traumatized from battle. Crime rates spiked, and overcrowding jails and asylums were costing the country a lot of money.

So how do you stop spending money on criminals? Give them a one-way ticket to the other side of the world, says Larry Powell. “Shannon Dawdy wrote a wonderful book called Building The Devil’s Empire, and she had a great phrase that I use—colonization by abduction—where they would empty out the mental hospitals and the prisons, and they would round up the vagabonds (of which there were a large number on the streets of Paris), and they would dump them here.”

An official ordinance was announced in Paris on November 10, 1718, that allowed local authorities to arrest those labeled vagabonds and send them to Louisiana. The first shipment of these forced immigrants arrived on Gulf soil September 1, 1719.

According to colonial records, these first New Orleans citizens included “violent disturbers of the public peace,” “a mad vagabond night prowler,” “a libertine who had threatened to kill his mother,” and a man “jailed for repeated sodomy.” Come on down, fellas!

Specific police units called the Bandoliers of Mississippi were created to round up these misfits. And these guys were often bribed; for instance, by a husband unhappy with a wife, or ex-friends who owed each other money. As a form of revenge, all someone had to do was accuse said enemy of being a vagabond in one form or another, and—poof—their nemesis was put on the next ship towards the Gulf.

You know how nowadays if a wealthy family has an unruly child they don’t know what to do with, they send the kid off to boarding school? Well, Louisiana was the French nobility’s version of boarding school.

“They thought this would be a kind of penal colony where they could reform criminals and vagabonds into the habits of steady industry and domestic bliss, marital bliss,” says Powell. “And of course it didn’t work out that way.”

By marital bliss, Powell is referring to the mass marriages that were forced on many of these immigrants before boarding the ship to the new world. His book reads:

“In the name of family values, they had been forced into mass marriages; after the ceremony the grooms would be marched in chains to waiting ships, while the brides rode alongside in carts.”

So, France thought, let’s force these people into becoming upright citizens. We’ll make them marry, start families, put them to work. And best of all, they’ll be out of sight, out of mind. But not for Bienville, who by this time was governor of Louisiana. He wrote his frustrations to the Crown:

“It is most disagreeable for an officer in charge of a colony to have nothing more for its defense than a bunch of deserters, contraband salt dealers, and rogues who are always ready to desert you but also to turn against you. And who think of nothing but returning to their homeland.”

Note: There was another group of forced immigrants in Bienville’s social experiment: enslaved people, many of them from Senegambia. From the get go, New Orleans wasn’t just a collection of misfits, it was a slave society. More on this in upcoming episodes.

With this unwilling labor force, progress was so slow in the first few years that maps were being made and sent back to Paris, without depicting New Orleans! So while Paris was sending Bienville their grotesques, the rest of the world was ignoring him completely. Talk about neglect…it’s like going to psychotherapy as an adult and returning to the first three months of your life, and the doctor wants to know things like, “was your mother working?” This does something to a city’s identity. Powell agrees.

“It’s true, we began as a foundling. We were orphaned and abandoned.”

Feeling abandoned by his benefactors back home, Bienville was paranoid that the unruly misfits, with no loyalty to him or his land, would desert him too. But there was no going back, especially for a convict without a dollar to his name. And so, although it wasn’t their choice, these orphans saw their arrival in New Orleans as a fresh start, a chance to reinvent themselves, to choose new names.

Powell says they would make up their lineages; they might be commoners, but simply putting a de in front of their name changes their status. And who would check? “I mean, you can’t go on the internet and do a background check,” Powell says. “We were a city of imposters in a way. That’s why Mardi Gras fit so well with our identity; we could always put on new masks.”

A decree from the King’s Council of State on May 9, 1720, who has ordered vagabonds, debtors, and fraudsters will no longer be sent to Louisiana. Credit Historic New Orleans Collection

Forced emigration of Europeans was finally put to a halt when the last ship of exiles delivered 81 women to Dauphin Island on January 5, 1721. That year marked other major changes that ushered the city towards legitimacy. The first census was taken, and engineer Adrien de Pauger came in to turn what was, in Larry Powell’s words, a swamp with intersections, into the designed grid that the French Quarter is today.

By this time, New Orleans was the most densely populated region in the Gulf South, with half of the people being enslaved Africans. So, this resettlement of dissenters marks the beginning of what writer Shannon Dawdy calls rogue colonialism—a society where, as Dawdy puts it, “the lines between the licit and the illicit, between law and disorder, were blurred.”

Yep, sounds about right.

TriPod is a production of WWNO—New Orleans Public Radio, in collaboration with the Historic New Orleans Collection and the University of New Orleans Midlo Center for New Orleans studies. Special thanks to Evan Christopher for the theme music.

Catch TriPod on the air Thursdays at 8:30 a.m., and Monday afternoons on All Things Considered.