For Writers Of Historical Fiction, Inventing New Orleans’ Past Can Come With A Price

TriPod: New Orleans at 300 returns with a story about George Washington Cable and the beautiful danger of writing New Orleans-based historical fiction.

“He’s the first really to introduce almost the exoticism of Creole culture, both white and black, and he was enormously popular—up there with Twain,” says Larry Powell, a historian and author.

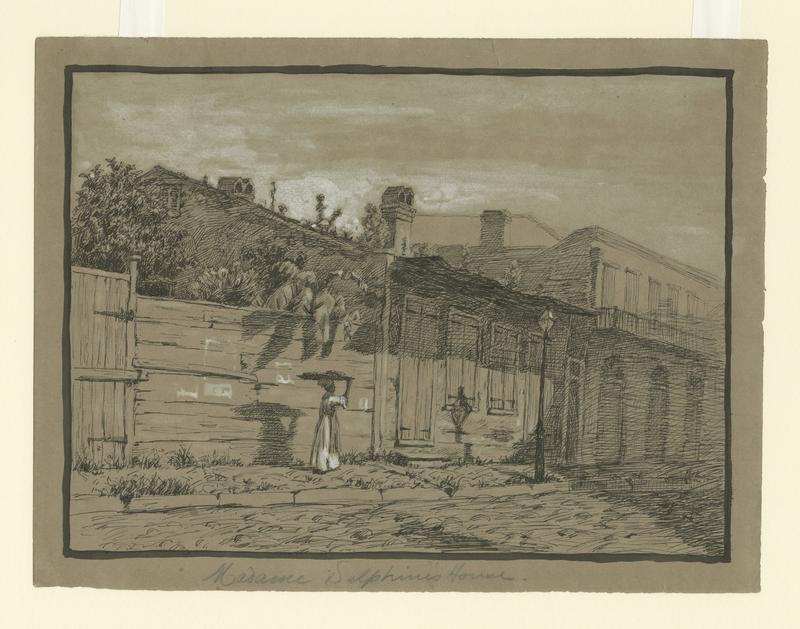

Powell is referring to Mark Twain, who is known by most people in this country. But how many people know who Cable was? Fewer. But this wasn’t true in the 19th century. Some call Cable the first modern Southern writer. A native New Orleanian born in 1844, he became the source for visitors interested in the city’s history. Even though Cable wrote fiction, tourists walked around with their maps and their Cable. His novel was their guidebook.

The Grandissimes: A Story of Creole Life is Cable’s most famous historical novel. Written in 1880, it depicts race and class relations in the city right after the Louisiana Purchase but is more of an allegory about the Reconstruction era and dynamics within the French Creole culture in the aftermath of slavery. The book focuses on various members of the Grandissime family made up of black, white, and mixed-race members.

Three quarter length portrait of a bearded man seated sideways on a chair. He rests his elbow on the chair rail and turns his head toward the left. He wears a dark jacket with a single row of buttons and striped trousers. He holds a cane in his right hand.

CREDIT COX, GEORGE / HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION

It was a novel that meant to change consciousness about race, a change Cable himself made. He was born into a wealthy family of slave owners and went on to serve in the Confederate army during the Civil War. But his experiences changed him, and he became an advocate for racial equality. This is when he started getting into trouble. White Uptown Creoles got pissed.

“I think the thing that rubbed them wrong the most was his suggestion that Creoles, as they say down here, had been tainted with a tar brush,” says Powell, “that there had been a lot of racial commerce and cohabitation. Grandissimes was a story about two brothers, one white, one black, and I think white Creole intellectuals were pushing back against the idea that Creoles had any African blood whatsoever.”

White Creoles sought to deny black family members and harden the myth that the term Creole just meant white. “Cable really exposed that myth in a way they found deeply uncomfortable,” says Powell, because Cable was documenting history while they were trying to mythologize it. “They were trying to distance themselves from their lineage.”

Many white Southerners worked to deny citizenship to men and women of color after the Civil War. And they made equal efforts to intimidate those who defended equality. Five years after he wrote The Grandissimes—remember, a fictional account—Cable felt so threatened by the hostility he faced in his hometown that he moved his family to Northampton, Massachusetts.

“He always thought the white South had a silent majority that meant to do well,” Powell says. “And he wanted to provide them ammunition. Well it didn’t work out that way. They drove him out of town.”

Fast forward to the 21st century, where most people don’t even know who George Washington Cable is, unless you’re a historical fiction writer, like Kent Wascom.

Wascom is a Gulf South native who recently published Secessia, set in New Orleans during the Union occupation in 1862. Hearing the name George Washington Cable, Wascom immediately jumps in…

“…who was run out of town! He was the first great bridge between New Orleans and the rest of the Anglo Celtic country,” Wascom says. “But the things he was accused of were being inauthentic and not representing the place properly.”

Cable was blindsided by the outrage, but Wascom expects it.

Kent Wascam

CREDIT KENT WASCAM

“Maybe it’s a sadistic impulse, but I’m more engaged when I’m angry. Because so much of our culture is hiding the ills or hiding it behind glorification, or behind marble or bronze, I enjoy dragging out the more wretched things.”

Still, Cable’s trajectory seems to haunt him. “I used to live in fear of historians standing up at a reading and saying, ‘you’re wrong! You’ve got this wrong,’” he says.

Wascom is not alone. Alys Arden is the author of the young adult novel The Casquette Girls. “I didn’t tell anyone that I wrote this book until about six months after it was published, and part of that was complete and utter fear of New Orleanians reading the book and hating me,” she says.

Somebody get these people a support group already! The Casquette Girls blends historical and paranormal activity and spans all three centuries of New Orleans’ lifespan, from the penal colony days to a post-storm apocalyptic landscape.

No wonder Arden has anxiety. But it doesn’t stop her from taking on dark matter, either. The title of her book is a reference to the first women sent to Louisiana, before the city was even founded. She explains further: “The history of the casquette girls coming over, you know which is the King of France sending these young girls over to basically marry men of the penal colony,” to keep them here, she says, because they were, like, “‘how are we gonna make a population? There’s no ladies!’”

Arden weaves this piece of history with other time periods, along with urban legends she heard growing up in the French Quarter.

“Taking an urban legend, I have to find out every single thing about it and the point in history that it happened.” So she calls up people like Lee Leumas, Archivist of the Archdiocese of New Orleans, and says, “‘so in this urban legend, x, y, and z happens, but I’m reading the Noir Code and, according to this, I don’t really know that this is possible, so…how far from reality would that be?’ And then we get to a scale, and I’m like, ‘okay, I can live with that.’”

Alys Arden in her New Orleans home on Esplanade Avenue

CREDIT LAINE KAPLAN-LEVENSON

Kent is also on board with taking liberties. “Not to put myself with too good company, but the Greeks learned their history from Homer!”

A fellow writer of historical fiction, Donna Gillepsie, once said about their shared genre:

“In crankier moments, I think expecting to learn history from a historical novel is like trying to learn botany from an impressionist painting of trees. There’s truth in those trees; it’s just not literal truth.”

Wascom agrees with these sentiments. “Fiction’s job isn’t the literal or the absolute. There is a responsibility there, though. You have to be true to the experience, if not to the facts.”

This rings especially true for Wascom, whose characters are people who existed in real life, which matters when people are using your book to get a sense of a time and place, as Arden also knows.

“I wrote the original draft of the book online, so most people reading it were not in New Orleans,” she says. “So there are a lot of people coming to the city or bringing the book or doing a tour from the book, going around the Quarter and stuff like that.”

Just like George Washington Cable! And as for Arden’s local audience?

“A hundred people just growing up in this 12-block radius right here are going to have different perspectives and experiences and argue which ones are right and wrong. So I definitely don’t think there’s a defining New Orleans experience. So if you hate it, and it’s not your New Orleans experience, that’s fine.” Just don’t make her live in Massachusetts, she says. “I want to be able to come home.”

Cable never did come back home, but he never stopped writing about it, either. His last work, written in 1918, is called Lovers of Louisiana, of which he always was one—just like his contemporary historical fiction writers, Arden and Wascom.

TriPod is a production of WWNO—New Orleans Public Radio, in collaboration with the Historic New Orleans Collection and the University of New Orleans Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies.

Catch TriPod Thursday mornings at 8:30 a.m. and Monday afternoons on All Things Considered. Subscribe to our podcast on iTunes and never miss an episode. While you’re there, please rate and comment—it really helps new people find the show.