Arson At The UpStairs Lounge

TriPod New Orleans at 300 revisits the UpStairs Lounge Fire in the wake of last month’s Orlando Pulse Night Club shooting.

In 1973, Clayton Delery-Edwards was living just outside New Orleans in Metairie, going to high school and, as he puts it, wrestling with “the G question.”

“You know by that point I figured out what it was, and I still wasn’t sure how it was done, but I knew what it was.”

Clayton’s talking about being gay.

“I was 15 years old, I had been gay-bashed pretty relentlessly and I didn’t even know what gay was, you know. But other people were already picking up on the…I was, I fit a lot of stereotypes.”

He says he was small, had a high pitched voice, “just check, check, check on the stereotypes.”

People’s perceptions of Clayton quickly turned his own confusion to fear, when he saw something on the evening news. “The regular programming was preempted because there was this horrible fire in the Quarter.”

This is the news story Clayton watched at WWL TV:

WWL TV had an anchor on, saying, “police arson squads are investigating the ruins of a bar where a fire last night killed 29 persons and injured 15 others.”

Its report stated, “two eyewitnesses who would not allow their faces to be shown told WWL TV newsman Bill Elder it was arson.” “And you say it was murder?” “I’m not going to say murder…I will say that what was done was done intentionally.”

“Even the earliest news reports described it as a known hangout for homosexuals,” says Clayton. “And so I thought: They’re going to kill me.”

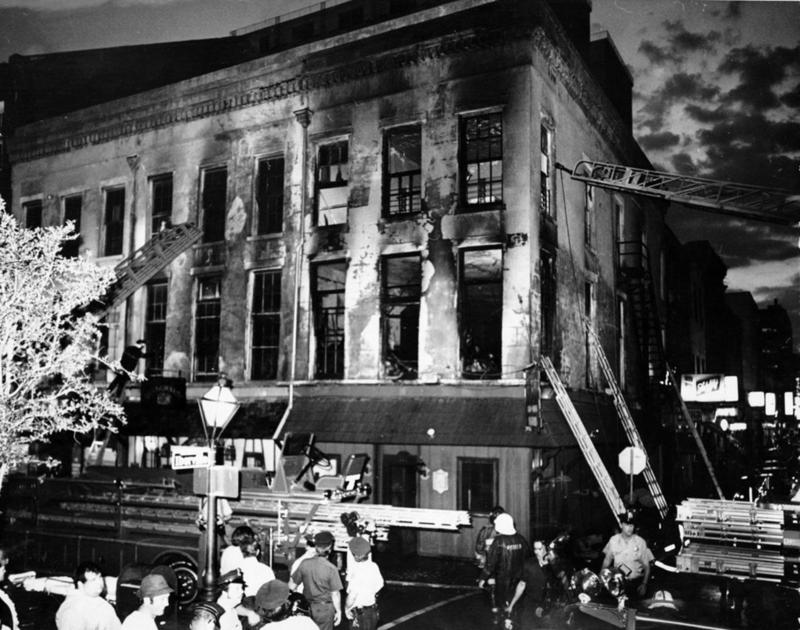

On Sunday, June 24th, 1973, the 2nd floor barroom of the UpStairs Lounge burst into flames.

Bill Larson, pastor of the New Orleans chapter of the gay-inclusive Metropolitan Community Church. Larson tried to escape from a window but became trapped by the framing and by some security bars. His only living relative—his mother—was so shamed by the news coverage identifying him as the homosexual pastor of a homosexual church who died in a bar catering to homosexuals, that she refused to claim his body.

CREDIT JOHNNY TOWNSEND

The bar, on Chartres Street where the Jimani Bar now stands, was having a benefit for the Metropolitan Community Church, or the MCC, the first church group to serve LGBT people. The bar was packed with MCC members and others celebrating the 4th anniversary of the Stonewall riots in New York, extended protests against police raids in New York City gay bars. Around 8 p.m. someone opened the door to the stairwell and—as many describe it—a fireball flew up the stairs through the door frame and quickly spread throughout the barroom. Thirty-two people burned to death. Many more were severely injured.

Royd Anderson was just a baby in New Orleans when the fire happened. He didn’t grow up learning about it in school. “As a kid I said, ‘man, this was the worst mass murder of gays in U.S. history, why am I not hearing about this?’”

The only reason he did hear about the fire is that his dad was a historian and used to take his kids on walking tours.

“He stopped us on the corner, and he said it was a gay bar, and somebody lit it on fire, and they have an idea of who did it,” Royd says. “But to this day no one was arrested.”

This baffles Royd, since there was a main suspect, Roger Nunez, a patron that night at the bar. “I’m puzzled to this day why he wasn’t arrested. He got in a fight at the bar; he got kicked out.”

“People claim to have heard him mutter, ‘I’m going to burn this place to the ground’ on his way out. Ten minutes later the place is on fire. He failed a lie detector test. He would get drunk a lot and make confessions to friends. He’d befriended a nun, Sister Mary Ladette. And she reportedly told the fire chief years later, like 25 years later, ‘this gentleman confessed this fire to me. Roger Nunez.’”

Roger Nunez committed suicide one year after the fire. The case was permanently closed. Royd made it his mission for people to talk about it and keep talking about it. That prompted his self-made documentary released in 2013.

That same year, historian Jim Downs was also thinking about how to get the UpStairs Lounge tragedy on

Lindy Quinton, usually known by his nickname, Rusty. Rusty was one of the few people thin and agile enough to squeeze between the bars at the windows and drop to the street. This was taken as he watched the fire in a state of horror. This picture ran on the front page of The Picayune. The caption read, in part, My Friends Are Up There.

CREDIT THE TIMES-PICAYUNE / THE PICAYUNE

the country’s radar. So for the 40th anniversary, he published a story on it in TIME Magazine.

That article became the first chapter of his book Stand By Me: The Forgotten History of Gay Liberation. The chapter is called The Largest Massacre of Gay People in U.S. History.

Unfortunately, as of June 12, 2016, that’s no longer true. Forty-nine people were shot and killed at The Pulse in Orlando, a popular gay club.

“I would have never imagined, in all of my editorial revisions and conceptualizations of the book, that there would be another massacre that would be larger than what happened in New Orleans,” says Jim. “I really thought that that type of massacre, that type of tragedy, was something that was in the past.”

After the deadly attack led by Omar Mateen at The Pulse, Jim wrote another story, this time an op-ed for the New York Times called ‘Before Orlando, There was New Orleans.’

He explains why.

“I thought this was an opportunity to really also show that bars, the places that many people often mythologize about gay life as these sites of celebration, this party culture, are also the sites of our oppression and terror.”

It took days to identify the UpStairs Lounge victims. Not only were they so badly burned, but many had fake IDs to protect themselves from being outed as gay. They were in the closet. Multiple families refused to claim their relatives’ bodies, and churches refused to host a memorial service.

Duane George Mitchell, who went by the nickname Mitch, with his lover, Louis Horace Broussard. Mitch was a divorced man, and his children were visiting from Alabama at the time of the fire. Mitch and Horace dropped the kids off to watch a movie on Canal Street and went to the UpStairs Lounge to see their friends. When the fire broke out, Mitch escaped, but realized that Horace was still inside. Mitch went back inside, but instead of saving Horace, the two men died together.

CREDIT JOHNNY TOWNSEND

A letter showing that St George’s Episcopal Church on St. Charles Avenue opened its doors for a memorial service immediately following the fire. St. Mark’s Methodist Church on Rampart held a larger service a week later.

CREDIT COURTESY THE ARCHIVES OF ST. GEORGE’S EPISCOPAL CHURCH

Clayton Delery-Edwards says when calls were made to local congregations, sometimes people laughed over the phone or just hung up without responding. This is what two National Metropolitan Community Church ministers—including founder Troy Perry, who flew in from California—experienced when making these calls. St Mark’s Methodist Church on Rampart Street eventually opened its doors and held a service a week after the fire. Reverend Perry also visited victims in the hospital. He remembers one horrific memory of this experience years after the fire, as told to StoryCorps.

“I remember going to the hospitals. One of them, a schoolteacher, burned so badly. He said, ‘well the school board just called me to tell me I was just fired from my job.’ He’d gotten the call while he was lying in the burn unit. He said ‘can you help me a find a job?’ I said absolutely. He was burned so bad I couldn’t imagine him living. I said ‘absolutely.’ He died the next day.”

Some news outlets quickly buried the story, especially TV. But Clayton commends some local reporters who continued to print articles on the fire.

“I give credit to people like Clancy Dubos and other journalists for the Picayune and the States Item for publishing sympathetic articles about all these dead LGBT people who, you know, the police chief dismissed as a bunch of thieves and queers.”

Not only did members of the press call out the negative comments and jokes going around, reporters also called out those not saying anything at all.

Royd Anderson says the top political leaders, such as then mayor Moon Landrieu, overlooked the incident. Of Edwin Edwards, who was the governor the time, Anderson says he “made no statement of public sympathy for the victims—nothing.”

Royd Anderson and Moon Landrieu both went to Loyola University, at different times.

“I remember seeing him at an alumni function. I said, ‘hey, look, I’m working on this documentary on the UpStairs Lounge Fire,’ and he said, ‘well, I was out of town at the time; I was in Europe. So I really can’t help you with that.’”

But Mayor Moon Landrieu came back from an out-of-town trip that same year when a sniper killed seven people at a Howard Johnson’s hotel on Loyola Avenue. Clayton Delery-Edwards remembers this.

“He cut his trip early and had a press conference in a remote location. He was in front of all the news cameras, he was in front of all the print journalists, he declared days of mourning for the city.”

But Moon Landrieu was perfectly happy to let the UpStairs Lounge massacre slide, Clayton says.

Today, Moon’s son Mitch Landrieu is now the mayor. He declared a day of mourning on the 40th anniversary of the fire. And, a few nights after The Pulse massacre, Mayor Mitch Landrieu attended a local service for those victims. So, times have changed. Within hours of the Pulse attack, the governor of Florida made public comments, along with other governors around the country, and POTUS himself. Obama extended condolences to the victims and their families.

Natalie Bennett, Green Party leader, showing solidarity alongside activists at the London vigil in memory of the victims of the Orlando gay nightclub terror attack.

CREDIT ALISDARE HICKSON / FLICKR

Jim Downs agrees it’s different but wonders just how different times are now. He considers Orlando.

“It was in the news cycle for a larger period of time. It made national news. So I think that’s a sort of major difference.”

More coverage is a good thing, but Jim says that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s good coverage. He found the emphasis on shooter Omar Mateen’s sexuality and relation to Islam a distraction from what he considers the more important pieces.

“Meanwhile there are families who were literally picking up the phone learning that their children are in the morgue, I mean, that’s the story. This story of homophobia, that children still don’t tell their parents that they’re queer. So it’s like, there are so many different stories to tell.”

Before Orlando, Clayton Delery-Edwards thought the younger generation could finally shed these anxieties.

“I didn’t think that LGBT people in their teens and twenties, now, experience the kind of existential fear that they could be wiped out simply because of who they were. That’s a fear that I grew up with and that my husband grew up with.”

He’s saddened that today’s queer youth still experience that same fear, which is why Royd Anderson, who’s also a middle school teacher, feels the need to talk about it with his students. He always teaches The UpStairs Lounge fire in his class, even though it’s not part of the required curriculum. He hopes one day it is.

A memorial plaque rests in the sidewalk where the Jimani Bar now stands on Chartres and Iberville streets in the French Quarter. The plaque memorializes the deadly attack that took place on June 24th, 1973, at the UpStairs Lounge, killing 32 people.

CREDIT HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION

TriPod is a production of WWNO, New Orleans Public Radio, in collaboration with the Historic New Orleans Collection and the University of New Orleans Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies. Special thanks to Evan Christopher for the opening theme music and to Pizza Delicious on Piety street for their additional garlicky support. Catch TriPod on the air Thursdays during Morning Edition and again on Mondays during All Things Considered. Hear TriPod anytime anywhere wherever you listen to podcasts, and write us a review on iTunes. TriPod’s also on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter at @tripodnola.