An Absolute Massacre: The 1866 Riot At The Mechanics’ Institute

TriPod: New Orleans at 300 returns to remember the 1866 massacre at the city’s Mechanics’ Institute. It’s part of a series of episodes on the Reconstruction era.

“White people, I believe, do not understand the mistrust that many black people in the United States have of police and of authorities.”

Bruce says this sitting at his little kitchen table in the Bayou St. John apartment he’s staying in while doing research in town. He’s a professor at Université Sainte-Anne in Nova Scotia and is working on translating a collection of 70 French language poems that were published during the Civil War and Reconstruction eras in The New Orleans Tribune, a radical newspaper run mostly by people of color.

Two of these poems were written in response to the 1866 massacre. “It was seminal in creating deep feelings of mistrust that I believe black people still have that they will not be protected, and even that they can be killed with impunity,” says Bruce, who didn’t learn anything about the massacre growing up in Shreveport in the 1980s.

“A lot of us really looked up to the Civil War as something that was glorious. We played Confederate soldiers, you know, those sorts of things. And it was only later through my studies and interest that I developed as a young adult that I learned that a lot of what shaped our world happened during Reconstruction.”

This is when Bruce started to see why black people in America were and are in fear of the police.

1866—one year after the Civil War ended—was a tense year. Louisiana Republicans wanted to explore giving blacks the right to vote. They called a convention to consider it in the state constitution. “It seems very noble, and in many ways it was,” says Bruce. “But everything was politicking, right? And people change loyalties strategically.”

Republicans, arguably, supported giving blacks the right to vote in hopes it would help their party maintain political power. Louisiana was under Union occupation during the Civil War and had a Republican governor by the end of it. But in 1866, Andrew Johnson was the president of the United States and a big fan of home rule—letting former Confederate states make their own decisions again—as long as they also obeyed federal laws. This concerned Republicans in the South, who felt they would lose ground under home rule. At such a pivotal moment, Republicans realized they needed the support of freed black men to maintain political power.

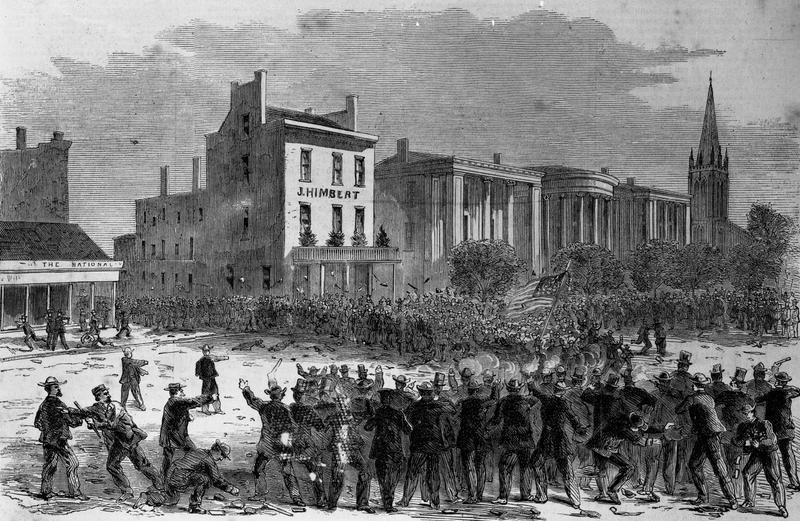

And they got it. Black men, women, and children showed up to support the lawmakers in changing the state constitution. “A procession of 70-100 black men had proceeded to this point. They organized themselves down in the Faubourg Marigny,” says Caryn Cosse Bell, a research professor at the University of New Orleans Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies. She stands on Canal Street, right where Burgundy turns into Roosevelt Way, to describe what happened on July 30, 1866, outside of the constitutional convention, when these freedmen, many of them Civil War veterans, showed up.

“When they got here, I guess about the middle of the block here, they were assaulted by white attackers,” she says. “They were verbally and physically assaulted; someone actually shot at them. They fired back, and no one was injured. They fought off the attackers and proceeded right down here on Roosevelt Way to what is today the Roosevelt Hotel. Back then it was the Mechanics’ Institute.”

This convention had been highly publicized. Everyone around town knew it was happening, whether they were for or against blacks gaining the right to vote.

Bell crosses Canal Street to the entrance of what is now the famous luxury hotel. “This is where the street was filled with men, women, and children, who were jubilant at the thought of an interracial democracy, the hopes of an interracial democracy.”

The parade of marchers had thwarted the mob on the other side of Canal, but once they made it to the Mechanics’ Institute, where the convention was taking place inside, they were beset by more violence. A gang of white supremacists and ex-Confederates attacked. Fire sirens went off, signaling police to attack. They were sent by the mayor.

“There was panic, because the police and firemen, armed, surrounded that building and began advancing,” says Bell. “The attack was premeditated. Lead police chief Harry T. Hayes had been recruiting policemen from Confederate veterans. They stormed in and started shooting, chasing people down the street.”

When the attackers finally ran out of bullets, nearly 50 people lay dead, mostly black.

Bell says more than a hundred were injured. “That’s very conservative though—it’s thought that as many as 200, maybe more, were injured in all of this.”

Federal troops had also been called in, well after things got bloody, and it was obviously too late. People lay limp, heads bashed in with bricks, broken bodies thrown from windows, landing on top of emptied bullet casings and abandoned knives.

Justin Nystrom is an associate professor of history at Loyola University, and co-director of the Center for the Study of New Orleans. “Of course as the saying goes, it was an absolute massacre. Because it was.”

Nystrom is currently writing about the massacre and says there were immediate consequences.

“The riot of 1866, as horrible as it may have been, was actually very useful to the Republican Party, because it gave them a concrete example of the kind of problems that the former Confederates were causing in the South. It was one of those instances where they couldn’t have done anything more detrimental to their own cause. And I think in a way these returning Confederates were given enough rope, just enough to hang themselves.”

He says the Mechanics’ Institute Massacre, combined with another massacre that happened two months earlier in Memphis, Tennessee, essentially served as a reset button for post-war policy in the South. These events were top stories in the national media and influenced voters who headed to the polls that fall.

“And of course they elect a radical super majority to Congress,” adds Nystrom. “The radical super majority enacts the Reconstruction Acts which break up the South into military districts. I often teach my students that if you don’t have the riot of 1866, you probably don’t have the 14th and 15th Amendments in the way that they appear.”

The 14th Amendment granted citizenship to former enslaved people in 1868. The 15th Amendment, giving black men the right to vote, passed in 1870. Despite the progress it helped achieve, the massacre was a tragedy. There were no convictions in the aftermath. Nobody went to jail.

This reminds Clint Bruce of many recent, contemporary incidents of police violence against people of color. “I’m thinking of Tamir Rice, the 12 year old who was gunned down. That was settled, it wasn’t considered a murder.”

And the country’s waiting to see what will happen to the officers who shot and killed Philando Castile, in his car in Minnesota, with his girlfriend beside him. And the day before that, Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge.

After the Mechanics’ Institute Massacre, The New Orleans Tribune continued to follow the incident for months, both in news coverage—and poetry. Remember those published poems written by Afro-Creoles that Bruce is translating? Camille Naudin was one of the most militant voices among the poets of the Tribune. He wrote a poem to commemorate the massacre called Ode to the Martyrs.

“It was written for the one-year anniversary of the 1866 Massacre, so it was printed on that day the following year,” Bruce explains, “the same day that there was a memorial ceremony at the Mechanics’ Institute. Ode to the Martyrs is really an elegy that enumerates a number of the victims who were killed, in pretty dramatic fashion, and celebrates their sacrifice.”

The poet mourns that victims of the mob were brutally massacred, while former Confederate leader Jefferson Davis remained alive—and free—at the time.

“There was a perception among Unionists that he was getting off scot free. In an earlier stanza he references former Black Union soldier Victor Lacroix, who is from a really well-known New Orleans family, who was pretty much torn to shreds by the mob. At the end he writes, ‘mais je dirai toujours mulâtres, noirs, blancs, Victor Lacroix est mort, Jeff Davis est vivant,’ which I’ve translated as, ‘but for mulattos, blacks and whites, this fact I must tell: Victor Lacroix is dead. Jeff Davis lives still.’”

TriPod is a production of WWNO—New Orleans Public Radio, in collaboration with the Historic New Orleans collection and the University of New Orleans Midlo Center for New Orleans studies. Special thanks to Evan Christopher for the opening theme music and to Pizza Delicious on Piety Street for their additional garlicky support. Catch TriPod on the air Thursdays during Morning Edition and again on Mondays during All Things Considered. Hear TriPod anytime, anywhere, wherever you listen to podcasts.