Why New Orleans Leaned Into Tourism

TriPod New Orleans at 300 returns with a two-part series on tourism, starting with the city’s relationship to the industry, and how we became dependent on it.

“Full disclosure…[in] Louisiana, the drinking age was 18, and in Alabama it was never,” says Connie Atkinson, Associate Professor of History at the University of New Orleans. She’s been living in New Orleans for decades, but before then she drove here looking for fun.

“The advertisements that tourists see in other places, other countries, promote New Orleans as a place apart. Lyrics in rock-and-roll songs—there are dozens and dozens and dozens that mention New Orleans as a place apart, a place of sin, this otherness that you can visit. For instance, Planet of New Orleans by Dire Straits: If you visit there, be prepared, for these people in planet New Orleans.”

For one reason or another New Orleans has always been a destination city…with a reputation, says Atkinson.

“Well it was a port city. People come in from everywhere. People are accustomed to strangers. New Orleans was a Catholic city in the middle of the Protestant South. The Catholics, for instance, danced. However, for Protestant America dancing was sinful, especially on Sundays. Particularly people from the Northeast would come visit and were shocked! And shock sells.”

Cities like things that sell. Especially when selling itself can be its bread and butter. Lolis Eric Elie speaks his mind while we sit in his backyard in the Treme. “One of the problems with being a city that depends so much for its life blood on tourist economy,” he says, “is you are inclined to give the customer more of what they want.”

He’s a native New Orleanian and was a staff writer for HBO’s show named after his neighborhood, Treme.

“If they come here on a Monday and enjoy the red beans and rice on Monday, and they start asking for them on Tuesday, the next thing you know, you’re selling them on Tuesday,” Elie says. If they find out that the Mardi Gras Indians or that the second line organizations have their annual parades on Sunday, well, ‘could they do it on Tuesday, because our conference ends on Wednesday?’ And all of a sudden you got folks doing that stuff.”

Lolis Eric Elie in his backyard in the Treme neighborhood of New Orleans

CREDIT LAINE KAPLAN-LEVENSON / WWNO

This is what frustrates Elie about the tourism industry. He says it all comes down to character versus caricature. “I define character as something real, innate, unstudied, not put on,” he says. “I define caricature as taking those moments of your character that you find most popular and exacerbating them and exaggerating them so as to make yourself more pleasing to your audience.”

The city didn’t always use its home grown culture as its main attraction. It was an evolution. “In New Orleans you didn’t have a dedicated tourism bureau until the early 1960s,” says Mark Souther, Associate Professor of History at Cleveland State University.

He says up until the mid-20th century, “there was this idea that, ‘oh, you know New Orleans kind of sells itself anyway.’” After all, he says, “we have Mardi Gras, we have the Sugar Bowl, you don’t really need to do that much. People find us just fine; our hotels are full.”

Elect “Chep” Morrison Governor poster

CREDIT HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION. GIFT OF MR. EDWARD H. ARNOLD AND MISS CATHERINE L. ARNOLD [1986.8.17]

After World War II, New Orleans wasn’t as important an economic power as it had been. Souther says Mayor Morrison wanted to restore that more than he wanted to restore old dilapidated buildings.

“He basically said, ‘I would gladly trade all this glamour and romance of the French Quarter for a few modern buildings.’ Of course, he’s looking at other cities like Houston and Atlanta and Dallas,” says Souther.

All the modern skyscrapers those New South cities built were filling with corporate jobs. Elie calls the emulation unfortunate.

“We have a problem with self-image,” he says. “We are constantly trying to be more and more like our inferiors. Our concept of progress is Atlanta and Dallas, all these places. I have yet to find anybody in Dakar, Senegal, in Paris, France, or Bombay, India, saying, ‘Lord, I can’t wait to get to Houston.’”

In the 1970s, the city was still less focused on preservation as an asset and more focused on big business for economic growth, especially oil. And in the 70s, there was an oil boom. This is where we get into two different types of tourists.

“We spent less money than Utah attracting discretionary tourists,” says Atkinson. By discretionary tourist she means someone who chooses where to go, as opposed to someone who ends up in a place circumstantially, such as for a conference. Even here, the convention crowd capitalized on New Orleans as a brand name destination city already. “They’re more likely to come to the conference if it’s here,” they thought.

This is why we see the throngs of lecture-attending, expo-booth, window-shopping visitors who take to the streets, lanyards swaying from their necks, during their off hours from the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, Union of Black Episcopalians, or Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, just to name three conventions taking place in New Orleans in 2016.

View of Mayor de Lesseps S. “Chep” Morrison and two unidentified men looking at proposed Civic Center model

CREDIT HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION [1988.161.7]

“Moon Landrieu took office in 1970,” says Souther. “And he’s saying, ‘yeah the French Quarter is a great place for tourism, and by the way, why don’t we really develop that and make it much more tourist friendly?’”

Landrieu, father of New Orleans’ current mayor, Mitch Landrieu, was one of the first to invest in tourist-driven development, particularly in the Quarter. He created the pedestrian walkways on either side of Jackson Square and the viewing platform that sits between the square and the river (all those steps next to Cafe Du Monde). And the Moon Walk along the Mississippi River, named after Mayor Moon, was another part of this effort to create a tourist space (not to be confused with Moon Wok, the Chinese restaurant on Canal Street).

“So he was looking to create fun zones, and he was not alone,” Souther says. “Other cities were doing these same kinds of things in the 60s and 70s. You have Ghiradelli Square in San Francisco. Then Boston in 1976 opens Faneuil Hall Marketplace. So all these things were happening at the same time. Old spaces being re-purposed for tourists.”

It was about the notion of progress more so than preservation, which often favored the visitor more than the local. Take the French Market, says Souther.

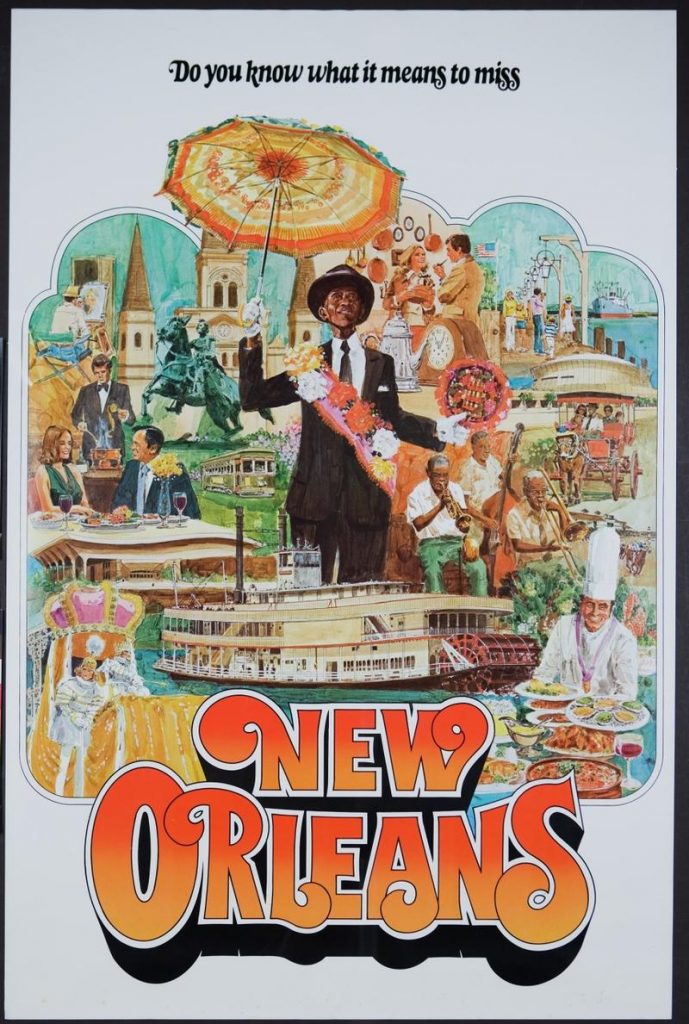

Poster promoting tourism showing a French Quarter scene viewed through an arch, showing an outdoor cafe, a jazz hall, pedestrians, a couple riding in an open sports car, a woman walking a dog, a man with a painting under his arm, a sailor talking to a woman, the bow of a ship at anchor in the river, the roofs of the Quarter, St. Louis Cathedral spires, and street lamps

CREDIT THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION [1988.118]

New Orleans has always loved its food, but it wasn’t always used as bait to lure visitors. This changed in the 1980s, says Connie Atkinson, when the oil boom came to a crashing halt.

“When the price of a barrel plummeted, people were out of work; it was a desperate time for the city,” she says. “So they started looking around for ways to attract the discretionary tourist.”

Atkinson says out of this desperation, the city went from overlooking its culture to hawking it.

“The slogan was, ‘come join the parade,’ which gave visitors the idea that our private cultural activities were open for them to participate in,” as if the city’s sending an open invitation.

“So it’s like ‘yeah, it’s granddaddy’s funeral but yeah, jump on in, have some fun,’” she says.

It’s dangerous to do anything out of desperation. New Orleans went from a triumvirate economy with a major port, leading in oil, and building a tourism industry, to really leaning in on tourism. That did create a lot more jobs.

“I would never question that,” says Souther. “but, it’s no replacement for having a diverse economy that has a lot of different kinds of jobs that are more rewarding and more stable. And it’s a hard mix to find.”

Lynnell Thomas grew up in New Orleans and is now Chair of American Studies at the University of Massachusetts Boston. She agrees with Souther and Atkinson that tourism became a central industry to make up for the lost industries, which is why everybody had to get on board.

“It required, of all New Orleanians, for us to buy in to the importance of tourism and how vital it is for the economy, that we needed to maintain it at any cost,” she says. “But we also buy into the idea that when tourism succeeds, everybody succeeds. And that hasn’t been the case.”

More on that from Lynnell coming up on the next TriPod…