If These Pages Could Talk: Touro Infirmary’s First Admission Book

TriPod: New Orleans at 300 returns to hunt down a rare artifact full of private and personal information. Laine Kaplan-Levenson goes on the search.

When you first walk into a hospital, before you can see a doctor, you walk up to a counter, where the person at the desk asks you a bunch of questions such as, who’s paying your bill, where do you come from, what’s your date of birth.

Touro Infirmary has been collecting this same information for more than 150 years.

Since the beginning, they’ve kept meticulous records about who exactly was walking through their doors and what was wrong with them. Let’s go find those records.

Florence Jumonville is the archivist at Touro Infirmary. Touro’s been around for forever. It was founded in 1852 by businessman and philanthropist Judah Touro. He established what was originally called the Hebrew Hospital of New Orleans to, as he put it himself in his own will, “treat the city’s indigent population.” The infirmary wasn’t where it stands today on Prytania Street; it was in the Warehouse District right on the river, where the convention center is now. Touro died two year later, but the hospital doors stayed open, and are still open today.

Touro Infirmary

CREDIT THE CHARLES L. FRANCK STUDIO COLLECTION AT THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION

I thought that alone was pretty unbelievable, but what’s really special about Touro isn’t just how old it is, it’s the number of artifacts that have survived all these years, and that now live in its archive, where we’ve just arrived. When I first walked in, Florence, the archivist, took me into this room full of old and intimidating medical instruments. There was an IV that still had congealed, brown liquid in the bag, as well as a bottle of nasty looking liquid marked Touro elixir. I asked Florence if she’d ever tried this ancient cough medicine.

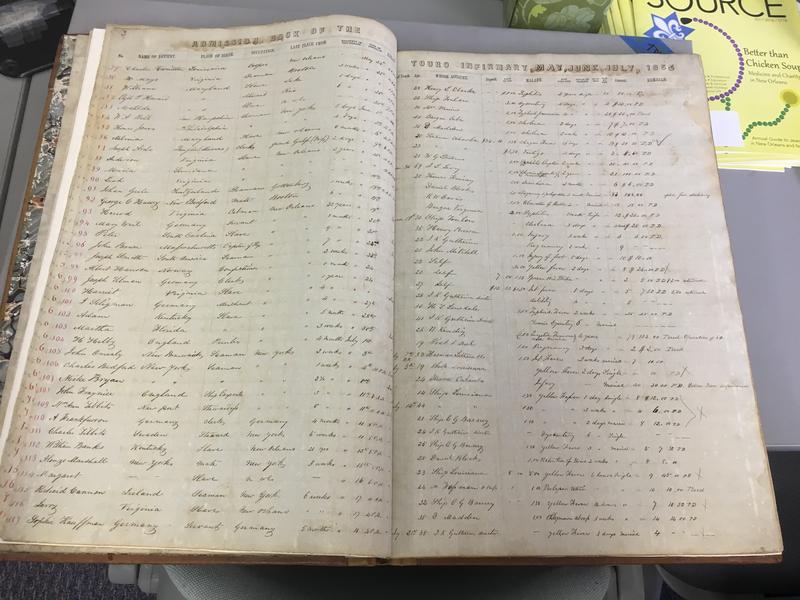

There were rusty scalpels, tongs, scissors, which, in their day, were state of the art. We looked around at all of this stuff, including a beautiful old desk that was once Judah Touro’s, an old tourniquet, and an eye chart in Hebrew lettering. But then, Florence led me to what I was really there to see: Touro’s very first admission book, containing all the information of every patient from 1855-1860.

I asked Florence what was special to her about the book. “The fact of its existence, really,” she replied.

This book is huge. It is about 22 inches high and 14 inches wide, almost two feet long, bound in brown leather, with every page lined and divided into columns, filled with names of patients, written in perfect script. And it’s got tons of personal details: place of birth, person’s occupation, place that they came from most recently, how long the person has resided in New Orleans (which was important because New Orleans was full of immigrants). It also tracked their age, who’s paying the bill, the day rate of a room, the ailment, how long they’ve been sick and, if they didn’t make it, the date of death.

The first person on the first page is Peter Peterson from Denmark—a Seaman. The last place that this man was in was Rio de Janeiro, and he had only been in New Orleans for three weeks when he was admitted. He’s 18 years old. He came in for dysentery, and he was at Touro for 21 days.

Lower down the first page, we have people from Denmark, Maine, France, Germany, Norway, New York, Virginia, Ireland, Sweden, Kentucky, Maryland, South Carolina, Florida, Georgia, Nova Scotia…of the forty people listed on the first page, only one was born in New Orleans. And the rest had basically just arrived. People had been in New Orleans for three weeks, two days, 12 days.

“At the time, hospitals generally were places where people went only if they had no relatives, friends, or neighbors who could look after them,” Florence told me. “Most people were cared for at home.”

In fact, Touro only had 28 beds at this time. It was small. “So many hospital patients were young men coming to New Orleans to seek their fortunes, or sailors arriving on ships,” which explains why there are so many riverfront jobs, such as dockworkers.

Marbling on the inside of the Touro admission book from 1855-1860

CREDIT LAINE KAPLAN-LEVENSON / WWNO

Leafing through the other listed occupations also helps paint a picture of this time period: jeweler, cabinet maker, bookkeeper, a planter from Point Coupee Parish, an apothecary, a contractor, a glazier (someone who makes glass), a charcoaler. (Florence guesses that’s someone who sold coal.) “There are lots of archaic occupations listed here,” she says, staring down at the page.

This is the type of record that historians lose their minds over, historians like Erin Greenwald. “I’ve never seen anything like it,” Erin says. It’s the level of detail that’s so mind blowing, such as these listed occupations. They tell us a lot about this pre-Civil War era. Erin says you’re getting dockworkers, “but you’re also right there where the ships come in laden with enslaved people who are being sold on the domestic slave trade.”

Touro Infirmary was strategically placed right on the river, because hospitals knew their main clientele—those that have been traveling and are largely without means—included enslaved people who were brought to New Orleans, many of whom arrived with health problems—fevers, breathing difficulties, chest infections, digestive problems.

Stephen Kenny is a historian in Liverpool, who’s written about the role of antebellum hospitals in the slave economy. Touro is one of many hospitals that admitted enslaved people. But the admission book is a rare record of their illnesses. That’s what makes the book so significant to Stephen Kenny. He says these were caused by the conditions enslaved people endured en route to New Orleans.

“So these are the effects of cramped and crowded unsanitary conditions and dietary deprivation,” says Stephen, “the suffering that people would have endured as they have been separated from families, forcibly transported, incarcerated, going through the facilities that fed the domestic slave trade.”

This starts to put into focus who the hospitals served, and who profited. Nearly half of Touro’s 28 beds were filled by enslaved people. I saw that myself, scrolling down a single page of the admission book—up to 20 enslaved people on one page, which is half of the 40 slots.

“Forty-five percent of all of Touro’s patients prior to the Civil War were actually enslaved,” states Erin. “And a significant number of them were being brought in by known slave traders so that they could essentially get their human cargo better, have them treated in a hospital, so that they could make more money off of selling these individuals.”

So, human beings were ripped from their homes and taken to New Orleans to be sold. Whether by ship or by foot, this journey was horrible. People were chained together, in unbelievably close quarters, for months. Many died along the way. Those that survived arrived in New Orleans sick and weak from physical and psychological torture. Traders wanted them to heal from the pneumonia, syphilis, diarrhea, and typhoid, that they contracted along the way, so they could sell them at the highest profit margin. I mentioned to Erin that I saw a lot of enslaved people in Touro’s register coming in with venereal diseases, and she said traders had an incentive to cure these diseases, especially the ones related to having babies.

“Because when a person is selling another human being in this environment, it is not simply their own labor that is being sold but the promise of future laborers.”

Their future children.

“If you have an enslaved person known to have a venereal disease, that automatically decreases their value, because it lessens their future worth.”

A woman who could give birth to a future enslaved person was worth more than a woman who couldn’t. So, half the time, doctors at Touro were rehabilitating enslaved people before they were sold at market. And slave traders were the ones footing the bill. It cost a $1 a day for an enslaved person, compared to $5 a day for everyone else.

Advertisement for Touro Infirmary; from Cohen’s New Orleans Directory for 1853; New Orleans: Office of the Daily Delta, 1852; CREDIT THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION, GIFT OF MRS. WILLIAM K. CHRISTOVICH, 98-173-RL

Traders were more than willing to foot the bill, because what they got out of it was a person they considered their property, that they could sell at a higher price. And Touro was good at this. In fact, enslaved patients were more likely to survive than Touro’s other patients. Historian Stephen Kenny told me that once an enslaved person returned to good health, Touro issued a certificate: “Certificates, expert testimony, which is again interesting in the New Orleans context because of the redhibition laws.”

Redhibition was a legal means of protecting buyers, a type of warranty that guaranteed the product that you purchased. This warranty allowed someone to return an enslaved person, if they were found out to be in poor health.

The warranty system was a Louisiana state law, unique to Louisiana. “It’s actually one of the very first lemon laws in the country,” adds Erin. “We associate lemon laws now with the automobile industry. But in Louisiana it has its roots in slavery. Every time an enslaved person was sold, a disclosure was included from the seller to the buyer indicating any sort of physical defect or malady.”

Some slave traders tried to skirt the warranty system by buying and selling sick people.

“There was an individual trader named Bernard Kendig who shows up repeatedly over and over again in this Touro register. He was known for going around town and purchasing enslaved people who had maladies, who had defects.” He risked passing them off as fully sound and healthy, so that he could make a bigger profit. We know this because Bernard Kendig got sued by multiple purchasers. So these warranties became vital in the business of slavery, and traders made sure to buy them—from Touro’s head doctor, Jay Bensadon.

“This was a man who was a physician but who also had the ability to provide warranties of enslaved people’s health,” Erin says. “So there are competing interests at play here.” This doctor was straddling the medical and insurance industry, through issuing these warranties. “This doctor is fully complicit in the slave system, because he’s operating on multiple levels to uphold and profit personally. I mean he’s not trading in individuals, but he is profiting from slavery.”

She says Touro profited, too. “Because if 45 percent of their patients are enslaved, that’s making up a good percentage of the hospital’s operating budget.” Of everything Touro’s admission book tells us about New Orleans, Erin says, it also shows “how deeply embedded the slave economy was in the American economy.”

Touro treated the city’s sick from the antebellum period to today—through slavery, Reconstruction, wars, hurricanes, floods. And it’s been a hospital serving the people of New Orleans that whole time—except for a few years during the Civil War, when it actually became an old age home for Jews, as a way to keep the Union army from taking it over. Had it stayed a hospital, the Union would have occupied it to treat their soldiers, but as an old age home, they left it alone. Unfortunately, we know very little about that whole time period, which only emphasizes the value of the admission book we do have. If the book hadn’t been saved, this entire chapter would have been lost. Historian Stephen Kenny says that’s the magic of the archives.

“People describe moments in the archives in various ways. Sometimes people speak about being transported back to the past, or the past as they imagine it. So it’s a moment full of a variety of feelings, a variety of emotions. It does feel like a tremendous privilege, and you reminded me, really, that it’s time to go back.”

And when he does go back, Florence Jumonville will be there. She spends all day thinking about how much the hospital has seen, and who’s come through its doors. She says along with the working class and enslaved populations the infirmary set out to treat, a bunch of famous people are in the records, too—such as Truman Capote, who was born at Touro; and Peggy Lee, who had double bypass surgery at Touro; and Professor Longhair, who was pronounced dead on arrival at Touro. “And Dorothy Lamour,” she adds, “the movie star notably from the road pictures with Bing Crosby and Bob Hope.”

She listed these notable patients as she closed the admission book from 1855-1860 and carefully placed it back into its case.

“And a jazz musician named Muggsy Spanier, whose life was saved by Alton Ochsner when Muggsy was touring here and collapsed with a bleeding ulcer and nearly died.”

Portrait of Muggsy Spanier, New York, N.Y. ca. Sept. 1946

CREDIT GOTTLIEB, WILLIAM P., 1917-, PHOTOGRAPHER. / THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

This was in 1938.

“He was here in the hospital for several months recovering and used his time to write a foxtrot titled Relaxin’ at the Touro.”

Relaxin’ at the Touro became the theme song of Muggsy’s group The Ragtime Band.

TriPod is a production of WWNO in collaboration with the Historic New Orleans Collection and the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at UNO.