Identity, Self-Expression, And Clashes Within The Enslaved Communities Of Colonial Louisiana

Last week’s TriPod saw an example of solidarity in opposition to slavery among people of African descent. But the dynamics within enslaved communities were complicated, and it was far from one big brotherhood. Allegiances were not automatic, and the story of a runaway named Francisque, who found his way to New Orleans in 1766, shows just that.

“It complicates our assumption that just because you were a slave you will have empathy towards another slave,” says Sophie White, a professor at the University of Notre Dame, regarding Francisque’s story. She discovered him while combing through the records of the Superior Council of Louisiana.

“In looking at the criminal trials, I discovered that most of them involved slaves who are accused of crimes. Other slaves would get to testify in court. And that was very intriguing to me, because we can get a sense of their words, how they express themselves, the stories they want to tell.”

This, White says, is a way to learn more how enslaved people related to and thought of one another and themselves.

Francisque came to town at a pivotal time. For roughly 30 years, between the 1730s and 1760s, slaves weren’t being shipped into the colony, so it was a tight knit group—everyone knew everyone. You think New Orleans is a small town today? Think about when there were fewer than 4,000 people.

This lasted until Spain took over the colony and resumed international slave trade with Africa and the Caribbean, which is around when Francisque rolls up. He’s from the West Indies, although originally he says he’s from Philadelphia. “He’s been purchased by one man who actually had been from Louisiana, and he’s sold to one of the two founders of St. Louis,” says White. “So he’s all over the place, he’s a peripatetic character, and I wish we could trace more of him.”

It’s when Francisque is on the boat heading to his new masters in St. Louis that he escapes and goes to New Orleans. Imagine him walking up and a bunch of heads turning, all with the same “who’s this guy?” look.

Francisque doesn’t really have a plan, or know how to answer that question, but he goes for it, says White.

“He tries to integrate in this local community, where he encounters problems because he is an outsider. And in a place like New Orleans and Louisiana, where you have a fairly stable population for the years that there have been no new influx of slaves, it’s a problem to know what to do with the slave and a problem for him to know how to integrate, and what the rules are, and what the customs are.”

He also straight up needs to survive. He’s a runaway: he needs shelter, he needs clothing, he needs to eat. So he goes to the market. White describes his first encounter with this group of slaves he’s trying to infiltrate. “He goes there to buy eggs. He pretends not to be a runaway and says he’s just buying eggs on behalf of his master, and he will come back with payment later, and he never does. He’s broken a rule, that he does not pay for the eggs.”

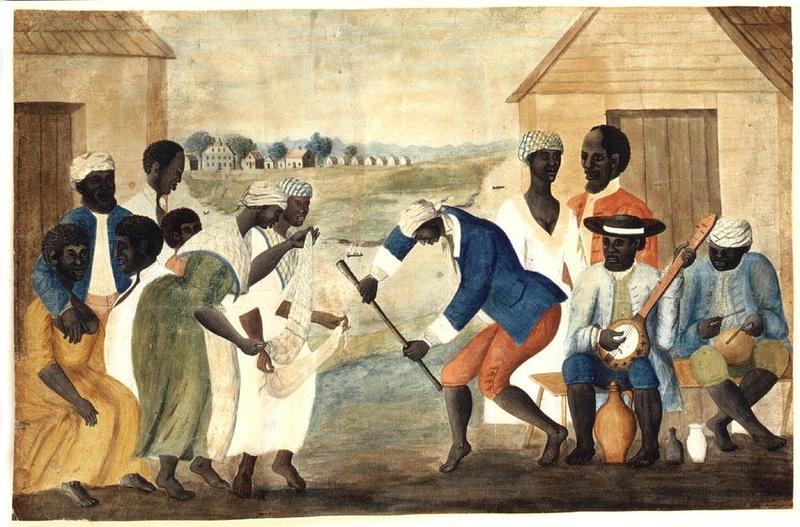

White says that might have been okay, but then Francisque shows up to a dance. At this time, slaves held social dances without the presence of their masters, or any whites. There was hardly any time or place for enslaved people to socialize and form romantic partnerships, but this is where most of that went down. So he comes through, and he’s noted for being very snappily dressed and for dancing with the women—not only dancing with them, but fronting all flashy like he could take care of them. The men are outraged. White continues with what happened next.

“And later on there’s another encounter where these two males come across Francisque, and he’s got a bundle of laundry. This is a bundle of laundry he’s supposed to have stolen. And they fight, and they threaten each other, and the final stage is they actually turn him in. And then the police take over. And then the courts take over.”

Francisque is accused of theft by fellow slaves. And he goes to trial.

Erin Kinchen is the reading room attendant at the Louisiana State Museum’s Louisiana Historical Center. She pulled Francisque’s file, starting with a testimony of an enslaved person against another enslaved person, Francisque, who confesses to being a runaway for a few weeks, but denies stealing anything.

Now we know Francisque’s story and how he perhaps failed to pick up on some social cues. But so what? Sophie White says: A lot. First, there’s jealousy.

Agostino Brunias. The Dance of the Handkerchief. ca. 1770-1780. Credit Carmen Thyssen-Bornesmisza Collection on deposit at Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza

“I think that’s a lot to do with it. So that’s the other big picture of this trial, because clearly he’s going there for courtship purposes—this is what happened at many of these dances and festivities. This is how you would meet your partners. When you have an outsider coming in and showing off and courting the women—I don’t know what the equivalent would be today—you know, taking someone home in a limo, maybe. You know, there are things that we expect, so this is what he has.”

This brings us to the main attraction of Francisque’s appearance, what White describes as “what Francisque has.” Handkerchiefs. Beaucoup handkerchiefs.

“So this is what he’s dealing with. He was wearing three or four handkerchiefs around his collar, his neck, and elsewhere. He’s not just wearing the neckerchief, they’re draped everywhere on him. Is he planning to give those to women he might want to court?”

White also points out that because these dances are exclusively for free and enslaved people of color, Francisque isn’t dressing up fancy to impress the white folks. He’s doing it for an audience of fellow slaves.

“I think most self-expression is targeted at a particular group, the group that you either come from or that you want to belong to. And I think when we look at someone like Francisque this is tricky, because he has a sense of some general rules—he knows about the importance of handkerchiefs—he has this artifact and this garment that he can use. But he doesn’t quite understand the finer points of how that plays out.”

“He tries to avail himself of the support that a runaway could usually get from the local community; they will often offer shelter or food or clothing. And he tries that. But it doesn’t really work out for him.”

Because although he picks up on some important cues, such as the significance of a handkerchief, he’s too consumed with his appearance and self-image (understandably so) and doesn’t seem to see that he’s angering the locals. You can’t ingratiate yourself with the locals while trying to show them up at the same time. And he doesn’t realize this until it’s too late. Back at the archives of the Superior Council records, Erin Kinchen found Francisque’s sentence given after a month long trial, which she read aloud:

“Francisque, convicted of breaking and entering at night and robbery, of running away, carrying firearms and threatening to shoot: and condemned to be hung and strangled and left on a post, and after 24 hours, his body thrown.”

Francisque’s story shows that it wasn’t always all for one and one for all in the enslaved community. The whites didn’t even know he was a runaway until a fellow slave drew attention to it by turning him in for his crimes.

Perhaps what’s more important here is what Francisque’s story says about individuality among the enslaved. While Francisque was bought and sold as chattel through the port cities of the Atlantic World, he made deliberate attempts to express himself and assert his humanity in a world bent on denying him those things.

TriPod is a production of WWNO New Orleans public radio, in collaboration with the Historic New Orleans Collection and the University of New Orleans Midlo Center for New Orleans studies. Special thanks to Evan Christopher for the opening theme music. Catch TriPod on the air Thursdays at 8:30 a.m., Monday afternoons on All Things Considered, or subscribe on iTunes.