The Women Who Fought For And Against The ERA: Part II

TriPod: New Orleans at 300 returns with Part II of its series on the battle over the Equal Rights Amendment. Listen to Part I here.

Last time, we left off around 1972, when the New Orleans feminist movement was working to pass the Equal Rights Amendment, which said: regardless of sex, there should be equality under the law. Women fighting for this legislation discovered that their main stumbling block was other women. The national face of that stumbling block was a woman named Phyllis Schlafly of Illinois.

So it’s 1972, the ERA seemed like it would pass, and then came Phyllis. She said this in a 2016 interview with the storytelling platform Makers just before her death. “Everybody who was anybody was for the ERA—all the prominent politicians all the way from Ted Kennedy to George Wallace. Three presidents: Nixon, Ford, Carter.”

She created the STOP ERA campaign. S-T-O-P for Stop Taking Our Privileges.

I spoke with Phyllis’s daughter, Anne Schlafly Cori, who is now the chairman of the Eagle Forum, the conservative interest group founded by her mother in 1972.

“And one of her reasons why was for my future,” Anne said. “She didn’t want my life to be less, to be diminished or less good than her life.”

Anne Schlafly Cori and Phyllis Schlafly.

CREDIT ANNE SCHLALFY CORI

By 1972, the U.S. Senate had passed the ERA, the amendment had gone to the states for ratification and passed 28 of them. Feminists only needed 10 more states to pass the ERA. So how did Phyllis go up against that?

How did she articulate that the ERA was actually a bad thing for women? Anne responds.

“Well, as I was growing up, I became closer and closer to the age of 18. And at 18, men register for Selective Service, which means they are eligible to be drafted into the military, and that was a key issue for my mother.”

Phyllis did not want her daughter drafted into the military.

Phyllis was a guest on the TV show Firing Line, founded and hosted by conservative William F. Buckley, Jr. in 1973. In the interview, she stated the “ERA won’t give women any more than they’ve already got, or have a way of getting. But on the other hand, it will take away from women some of the most important rights and benefits and exemptions we now have.”

When Buckley asked for an example, she replied: “Well a great glaring example on which there’s full agreement between both the proponents and opponents is the matter of the draft. Women are exempt from the draft. Selective Service says only young men of age 18 have to register, but the ERA will positively make women subject to the draft and on an equal basis with men.”

Phyllis had opponents of the ERA saying, “hey you want this ERA thing? Well then get ready to send your daughters off to Vietnam.”

Janet Allured, Professor of History at McNeese University in Lake Charles, Louisiana, said that caused a lot of people to say, well no, I’m not sending my daughter to Vietnam. Janet said that ERA supporters responded by arguing that you shouldn’t want your son to be forced to go to Vietnam if he didn’t want to go either.

But that wasn’t the only threat the STOP ERA campaign used to stoke fear.

“For example, they said that women would lose their right to alimony,” Janet said. “They said that the Equal Rights Amendment would force women out of the home, to get into the workforce, to go get jobs. They said that it would force women to go to the bathroom with men—this is what is called the potty issue.”

I asked Clay Latimer, a member of the Louisiana second-wave feminist movement, about the potty issue, and she told me, “people don’t believe that we really, really had to sit around and talk to men about bathrooms.”

The people Clay’s referring to are people today who are looking back on the second-wave feminist movement.

Clay’s opponents argued that the ERA would erase single sex public restrooms and replace them with unisex toilets. She remembers the potty issue dominating ERA debates in Louisiana even more than the threat of the draft. “And there was a woman, and she was at the legislature talking to one of the men who she knew socially and said, ‘now I want to talk to you about the ERA, and I don’t want you to talk to me about the potty. I’ve heard enough about the potty, so tell me really what the problem is!’ So yeah, nationally, everybody in the country was dealing with this bathroom issue.”

Louadrian Reed is another veteran of the feminist movement. “I mean we were fighting for everybody,” she said. “We weren’t fighting for any one person.”

But Phyllis Schlafly, the ERA’s arch nemisis, didn’t understand why anyone was fighting for anything.

“She said she didn’t need any rights. They had everything they wanted. Why should you rattle the cage, you know?” Louadrian said this explains why most African Americans in Louisiana supported the ERA.

And Professor Janet Allured says it’s a fact. “Every poll showed that African Americans supported the ERA in greater numbers than white Americans did. And the reason for that is that so many black women worked, because the men didn’t make enough money. There was so much discrimination against them and had been for decades, that men were severely underpaid. And so black men understood that their communities will be better off if their wives or partners are not discriminated against.”

This may be why the ERA had the support of Dorothy Mae Taylor, the first African-American woman to serve in the Louisiana House of Representatives. She was one of two women in the House. The other woman, Louise Johnson, was a staunch ERA opponent. So despite Dorothy Mae Taylor’s supporting the ERA, Louisiana didn’t ratify it. It passed the State Senate but not the House. But it was still on the table nationally, and in 1977 it was just three states shy of passing. On June 18th, 1980, a critical vote was up in Illinois, Phyllis Schlafly’s home state. The House of Representatives voted on the Equal Rights Amendment, and fell 5 votes short of the necessary ⅔ majority required for passage.

That was a no go for Illinois, and no state after that voted for the amendment. So the country was three states short when the ratification deadline rolled around. On June 30th, 1982, the ERA officially failed.

Anne Schlafly Cori says her mother’s legacy was giving a voice to what was known in the 70s as the silent majority, “the people who just kind of went along and did their lives but never actually spoke up and participated in politics. The role model that she presented to women to get up and do things was tremendous.”

She knows her mother was a polarizing figure and says that had a positive impact on her.

“It impacted me a great deal because I have no fear of bullies. People can say anything to me or do anything to me, and it just washes right off of me, and that’s what I learned from my mother. As my mother used to say, ‘I’m not gonna let those slobs ruin my day.’”

The same night the ERA failed, Phyllis Schlafly held a celebratory gala in Washington, D.C. I found an article about the party in the Washington Post. The article begins:

“The band played Somewhere Over the Rainbow as Phyllis Schlafly, leader of the nation’s STOP ERA forces, slowly descended the stairs of the Shoreham Hotel’s Ambassador Room, waving and beaming, radiant in white butterfly sleeves and a long strand of pearls. She grabbed a cluster of balloons, her eyes glistening with tears, then walked into a halo of television lights.”

Meanwhile, feminists in New Orleans were preparing a jazz funeral to mourn the death of the ERA.

Scene from the Jazz Funeral mourning the death of the ERA in 1982, outside Armstrong Park

CREDIT ERA NEW DAY NEWSLETTER PAGES. ERA — A NEW DAY! JAZZ FUNERAL AND CELEBRATION NEWSLETTER. / PAT DENTON COLLECTION, NEWCOMB ARCHIVES TULANE

Fast forward to today. There’s a revived effort around the ERA, and some states are again pushing for it. Nevada just passed it in March 2017.

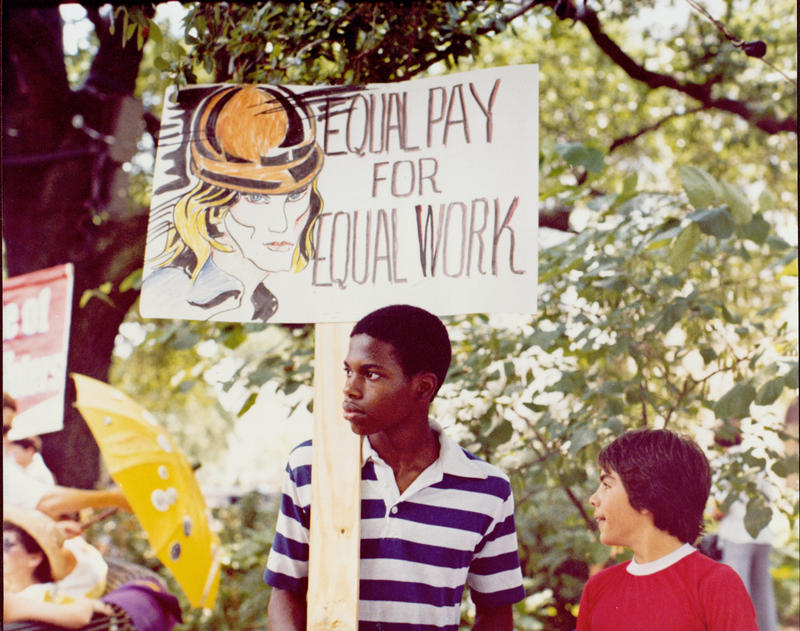

And here in Louisiana, feminists are still pushing for the ERA, but they’re really focusing on another piece of legislation: The Equal Pay Bill.

Louisiana Governor Jon Bel Edwards scolded the state legislature on April 10th, 2017: “We should all be offended that Louisiana has the highest gender wage gap in the country with women making only 66 cents for every $1 a man makes. It’s a simple and unassailable idea: Pay a woman, who has the same job and similar qualifications, the same you would pay a man. It is that simple.”

But just like with the ERA, some that oppose the Equal Pay Bill are women, such as Renee Amar, the Director of Small Business for the Louisiana Association of Business and Industry.”

Renee made it clear to me that her association supports equal pay for women and men, but she says there’s already a Louisiana state law on the books that bars discrimination in the workplace based on gender and wages. So, if women have a problem, she said, “they have an avenue on a state level if they want to sue their employer. They have an avenue on the federal level if they want to sue their employer.” Renee said there’s no way that the pay gap is based on widespread discrimination against women. She said it’s based on other things, such as maternity leave and women not advocating for raises. But don’t blame the businesses. “I understand that there are always going to be a few bad apples, and we [The Louisiana Association of Business and Industry] believe that the laws take care of those few bad apples.”

To which Governor Jon Bel Edwards responds: “When you hear, ‘well, we already have laws on the books to address this,’ if the laws we have were adequate to the task, we wouldn’t be last in the country.”

Renee said that if you really want to close the wage gap, it must be through education and training on salary negotiation.

There are three equal pay bills currently pending hearings in the Louisiana Legislature. All over the country, people who identify as feminists and those who don’t are asking questions about women’s rights. What should we be fighting for that benefits the entire gender? Does legislation actually improve people’s lives? What is real equality?

I asked Anne Schlafly Cori what advancement, if any, would she like to see for women in her lifetime?

“You mean we’re not already on top of the heap? Because it sure seems like we are to me,” she said. “I mean, what are we missing in our lives?”

I wondered how the three million people who went to women’s marches around the world in January would respond to Anne’s sentiment.

Louadrian Reed watched those marches on her television that day. I asked her the same question I asked Anne: what she’d like to see happen for women in her lifetime. “A female President. Or, even in New Orleans, a female mayor,” she said. “Or governor!” She said that would be nice, too.

TriPod is a production of WWNO, with support from the Historic New Orleans Collection and the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies. Subscribe to the podcast!